We expressed it from the beginning of our newsletter, the possibility of virtually visiting the world's cultural offer is here to stay. At that time, driven by the mandatory confinement imposed by Covid-19, but also virtuous in itself, by the opportunity to do it without too many barriers. This phenomenon also encouraged the development and visualization of numerous initiatives that are now available on the Internet, waiting to be detected; their most important problem, immersed in a sea of opportunities.

Among them, we want to invite you to discover a proposal that will surprise you: The Hall of the Rejected. “A project by Nicolás Martella whose purpose is to publicize the reserves of remaining works that have accumulated in the Palais de Glace since its creation. Its main source of nourishment has been the visual productions abandoned by their owners when they were rejected by the National Visual Arts Hall” writes Joaquín Barrera, curator of this particular project, which is now exhibiting its virtual format: SEE

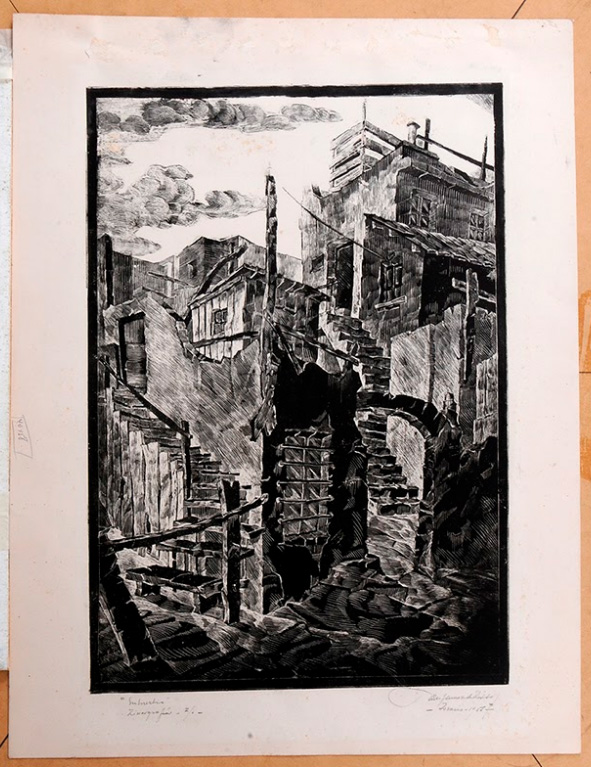

Until 2014 -that is, during the first one hundred and three years since the opening of the National Hall in 1911- participation in the main Argentine visual arts contest was carried out physically. The artists had to send their works to be evaluated by the jury. Starting in 1932, the Palais de Glacé was the venue for the Salon, so the works came from all over the country. A small and select group was chosen, selected, and the rest, that "leftover" that did not meet the expectations of the jury, was marked with a stigmatizing red "R" - for "rejected" - on the label attached to the back. More than 1,500 works make up this collection of remnants, which no one ever removed. “Doubly rejected. First by the jurors and then by their owners, who did not go looking for them,” explains Nicolás Martella, an Argentine artist who had already been working with discarded images in previous projects. In 2017, the institution carried out a final selection and purification of these remnants for their possible patrimonialization, and that is the set of pieces that make up this virtual exhibition, this Hall of the Rejected, 219 works dating from 1934, the first year of the National Salon at the Palais de Glacé, until 2014, when the initial submission of works began to be digital.

The name of this exhibition comes from the emblematic Hall of the Rejected (Salón des Refusés) in Paris in 1863. That event is a milestone in European art, and articulated with the birth of impressionism and the arrival of modernism. The story goes like this: by decision -of political overtones- of Emperor Napoleon III, the artists not selected by the French Academy of Beaux-Arts to participate in the Paris Salon would be exhibited in an adjoining room for the public and critics to judge. There, Luncheon on the Grass by Edouard Manet was presented, today an emblematic work, which at that time aroused, along with others, both admiration and scandal.

The National Hall in our country, born the year after the centenary and its great celebrations and exhibitions, coincides with the arrival of modernism and cosmopolitanism in the Argentine art scene. Like the one in Paris, from its birth it generated admiration and rejection. Much has been written and continues to be written about it, about its exclusive or inclusive role, open and federal or elitist, and even as legitimizer of the status quo. The critic Mario Gradowczyk analyzes the matter, in a dialectic that oscillates between the positive position "the Hall as a lighthouse" and the negative, "as a black hole". He writes: «If we place ourselves under a screen illuminated by the optimism of the elites, mostly from Buenos Aires, the Salons constitute dignifying elements of Argentine art, not only because of the vicarious and honorary aspects that having been accepted by juries made up of personalities entails. of the official world, but for the generosity of the prizes. It is possible to visualize each room as a luminous beacon that marks the course and illuminates the trajectory of Argentine art, preventing it from running aground in "dangerous waters." The fearsome keepers of the National Commission of Fine Arts not only exercise control of the National Salons, but also the directors of the museums and art academies and schools. Another alternative is also possible, to visualize them as black holes whose enormous gravitational forces devour any "star" that invades their zones of influence, sinks destined to destroy any innovation. Very few artists resist walking through this perverse field full of lighthouses and black holes». (1)

As in Paris, the excluded artists also organized alternative salons in Buenos Aires. In 1914 the IV National Exhibition awarded the painting Los mantones de Manila by Fernando Fader -today in the National Museum of Fine Arts- and rejected two sculptures by Agustín Riganelli. Several artists accused the Salon of rewarding mediocrity and conformism and rebelled against the admission and award system used in national painting salons, broke with the Academy and organized a parallel Salon in La Boca, without awards, which they named "the Recused Hall”. It was chaired by Florencio Sturla and José Arato, Santiago Palazzo and Abraham Vigo participated with his works, while Benito Quinquela and Agustín Riganelli joined. Four years later, with the incorporation of Adolfo Bellocq and Guillermo Fació Hebequer to the group of dissident artists, a second edition called “Salón de Independientes” was held. “Due to the criticism received in the initial salons, the regulations are modified and other members chosen by the exhibitors are incorporated into the official jury, with the exception that they had to be chosen from among those who participated in at least two previous salons. This maneuver sustains for many years the elitist character of the selection of works and the awarding of prizes”, writes again Mario Gradowczyk (2). Some time later there was an advance in the selection and award process: by the mere fact of sending work to the Salon, the artist was enabled to vote among a group of possible jurors.

Room V: “The body and its period variations”. Sculpture.

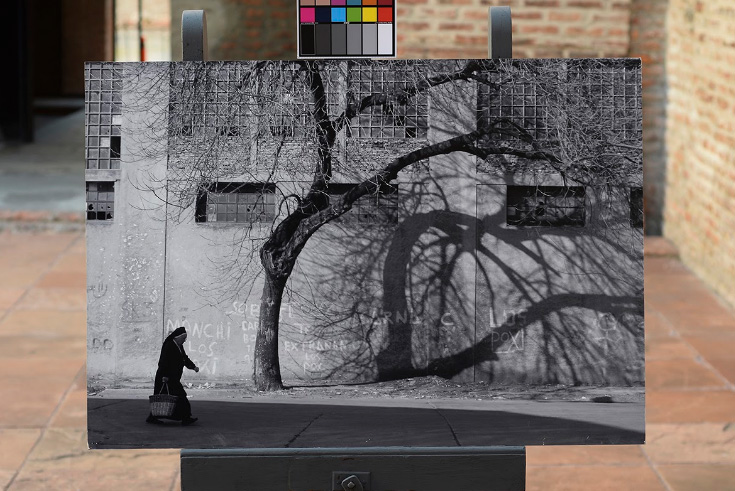

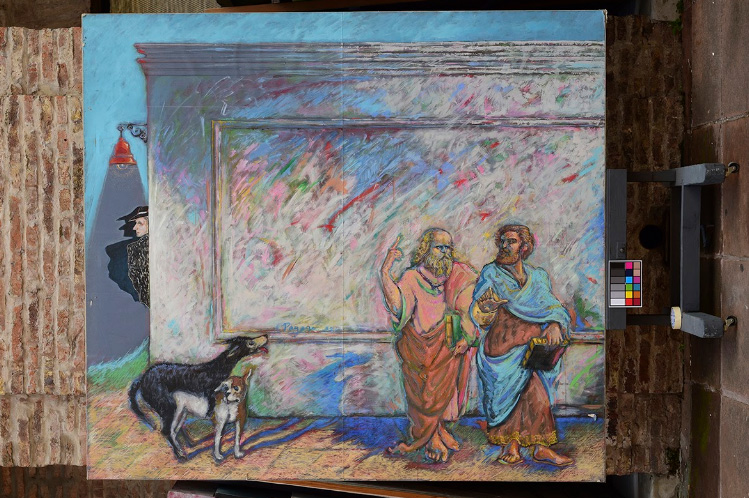

Let's go back to the recommended exposure. His works do not integrate either of these two groups, neither that of the chosen ones, nor that of the rejected reactionaries, thus expanding the panorama of national artistic production. "There are no proper names, no order of importance, no ascending or descending aesthetic evaluations," writes Joaquín Barrera in the opening text of this virtual exhibition. As in the Salón des Refusés proposed by Napoleon III, these works are now exhibited hanging (virtually) in eight rooms, each with a different colored wall, "if we presented them in a real museum, with an analog hanging, they would represent eight giant rooms full of works and stories to tell”. There are drawings, paintings, photographs, prints and sculptures of various sizes and forms of presentation. “They are all living together from curatorial nuclei that we define together with the artist -Martella and Barrera conclude- They are all here because it is an act of vindication of the discarded image but also because it is a way of showing that, beyond the limits of the inside and the outside and of the aesthetic, technical and formal assessment that the contests presuppose, the great poetic nuclei of the history of Argentine art are always the same and that there are no differences between no outside and no inside. It is that in these works that we are now presenting an insistence on certain themes is reflected. The landscapes of Argentine geographic biodiversity, patriotic education, oneirism and psychoanalysis, political violence and memory, essays on bodies, scenes of daily life and work, naive painting and abstraction ─transcendent poetics for national visual production─ are the central nodules that we could glimpse as soon as we came into contact with the material. These works, left aside by the judges and the artists and recovered by Nicolás Martella, today propose to continue putting into debate what is and what Argentine art has been talking about for a few decades, even when they have been left out of the history of the Salon.

A painting from the same Room VII.

Here is the link to visit this exhibition: HERE

Notes:

1. Mario Gradowczyk: The National Salons and the Avant-Garde: neither hysterical futurisms nor sickly and depressing painting. The evolution of the National Salons between 1924 and 1943. In Ramona, Visual Arts Magazine, Argentina, N. 42 (July 2004).

1. Mario Gradowczyk: Ob. Cit. July 2004