The spirit of the early 20th century in Italy, through the magazines and art of the time, in an exhibition at the Galleria degli Uffizi

In the last installment of Hilario I shared some experiences from the recent trip to Italy [1]. In that story he linked experiences in Turin and Florence to previous memories, the trip as a reunion with what was already known. I now share with you another moment from that visit, which could be described as the opposite: a surprising discovery, absolutely unplanned.

We were preparing to visit the Galleria degli Uffizi, in Florence. Central point among the desired destinations, the museum that occupies the first and second floors of the great building built between 1560 and 1580 by Giorgio Vasari, protects one of the most outstanding art collections on the planet with its large sunny gallery with Greek and Roman marbles, and the collection of Italian paintings from the 14th century and the Renaissance that includes masterpieces by Giotto, Piero della Francesca, Beato Angelico, Filippo Lippi, Botticelli, Leonardo, Raffaello, Michelangelo and Caravaggio, as well as incredible pieces by German, Dutch and Flemish painters . These works were our objective. From the perspective that I mentioned before, we would encounter Botticelli's genius in The Birth of Venus and Spring, for example. However, upon entering the museum we were surprised by a temporary exhibition titled Magazines. Culture in Italy at the beginning of the 20th century, which occupied new rooms built on the ground floor. And our trip to the Renaissance suffered - rather enjoyed - a surprising turn towards the avant-garde of the beginning of the last century.

We read in their curatorial text: «Deep minds, sharp pens, complex personalities, sometimes incendiary, all very different from each other but united by a fundamental characteristic: having (re)animated and fructified, with the magazines that they themselves founded and directed, the intellectual and political debate of the country in the first decades of the last century. Now, for the first time, a museum describes and narrates in its entirety, through the pages of its own protagonists, this restless and fertile period, fervent with ideas, visions, provocations whose genius and avant-garde scope has resisted the wear and tear of time and continues to generate fruits today. The exhibition was organized by the Uffizi together with the National Central Library of Florence, curated by Giovanna Lambroni, Simona Mammana and Chiara Toti. More than 250 works were exhibited in the rooms, including oil paintings, drawings, engravings, sculptures, and a complete overview of the most influential cultural publications that appeared on the peninsula during the first third of the 20th century, represented in display cases with magazines, pamphlets, loose and books.

The great Florentine revue season began in 1903, inaugurated by Giovanni Papini and Giuseppe Prezzolini's Leonardo (1903-1907), which brought together young intellectuals united by anti-positivist idealism and driven by the desire to undermine the culture of the time. Also in Florence was born Il Regno (1903-1906), founded by Enrico Corradini, the first important press organ of Italian nationalism. He was followed by Hermes (1904-1906), a literary magazine inspired by D'Annunzio. In the same fruitful year of 1903, the first issue of La Critica (1903-1944) by Benedetto Croce was published in Naples, with the intention of developing a critical activity guaranteed by the authorized presence of Croce and Giovanni Gentile. Once Leonardo's restless phase had passed, Giuseppe Prezzolini founded La Voce (1908-1916) in Florence, a magazine destined to play a central role in the Italian cultural and political debate. Another great publication of the time, which we see in the exhibition, was Lacerba (1913-1915). Protagonist of the Florentine futurist season and its memorable evenings, the “Lacerba” group organized futurist exhibitions between 1913 and 1914 that brought to this city the works of Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini.

Lacerba Magazine. Photography: Courtesy Galleria degli Uffizi.

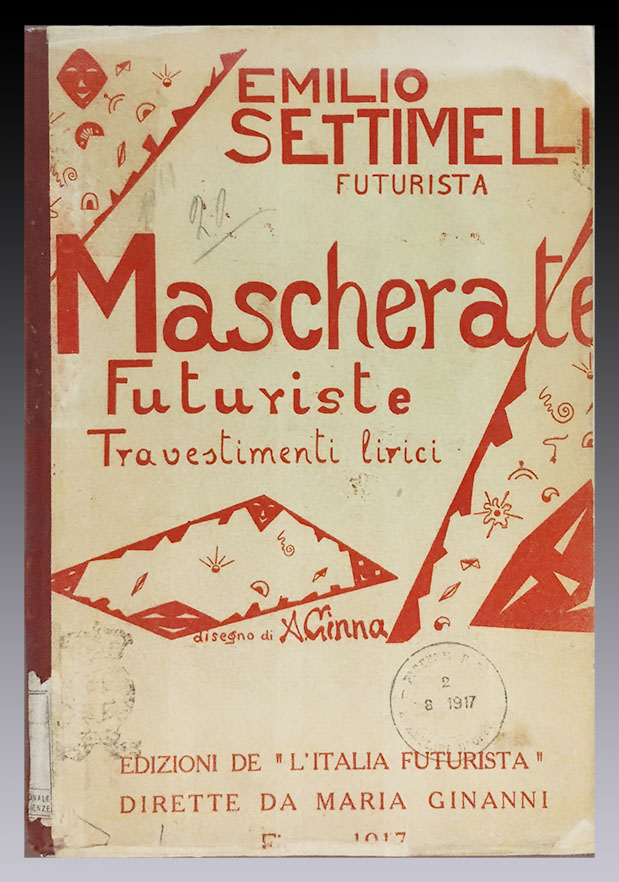

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti [2], together with Sem Benelli and Vtaliano Ponti, they founded the magazine Poesía (1905-1909) in Milan in 1905. The emblematic Futurist Manifesto was published there in 1909, turning the magazine into the organ of the movement. The Florentine response was L'Italia Futurista (1916-1918), founded and directed by Emilio Settimelli and Bruno Corra, later also with Arnaldo Ginna, where ample space was dedicated to Marinetti's writings.

In addition to the fundamental exhibition of the magazines, as I mentioned, the exhibition hung paintings, such as Pino sul mare, an oil painting by Carlo Carrá from 1921. I read on the exhibition poster: «"I no longer harbor any type of prejudice. I return to the forms "primitive and concrete. I feel like the Giotto of my time," Carrà wrote to Papini in June 1915, expressing his adherence to a new model of formal simplification that was to be defined even more in the postwar years in paintings of capital importance. like Pino by the sea, formerly owned by the musician Aldredo Casella." And I thought: Alfredo Casella!, the author of the great treatise The Technique of the Contemporary Orchestra that I have consulted day and night for years, and that occupies a place privileged over my piano.

By Carlo Carrà himself, together with Marinetti, Boccioni, Russolo and Piatti, is the controversial Sintesi futurista della guerra, from 1914. It is part of Guerrapintura: political futurism, plastic dynamism, 12 warrior designs, words in freedom, published in Milan by Edizioni futuriste I said “Poetry” in 1915. We read in Synthesis…: «We glorify war, which for us is the only hygiene in the world (1st Manifesto of Futurism), while for the Germans it represents a fat belly of crows and hyenas. We are not interested in ancient cathedrals; but we deny medieval Germany, plagiarist, stupid and devoid of creative genius, the futurist right to destroy works of art. This right belongs only to the Italian creative genius, capable of creating a new and greater beauty on the ruins of ancient beauty».

Futuristic synthesis of war. Milan, 1915.

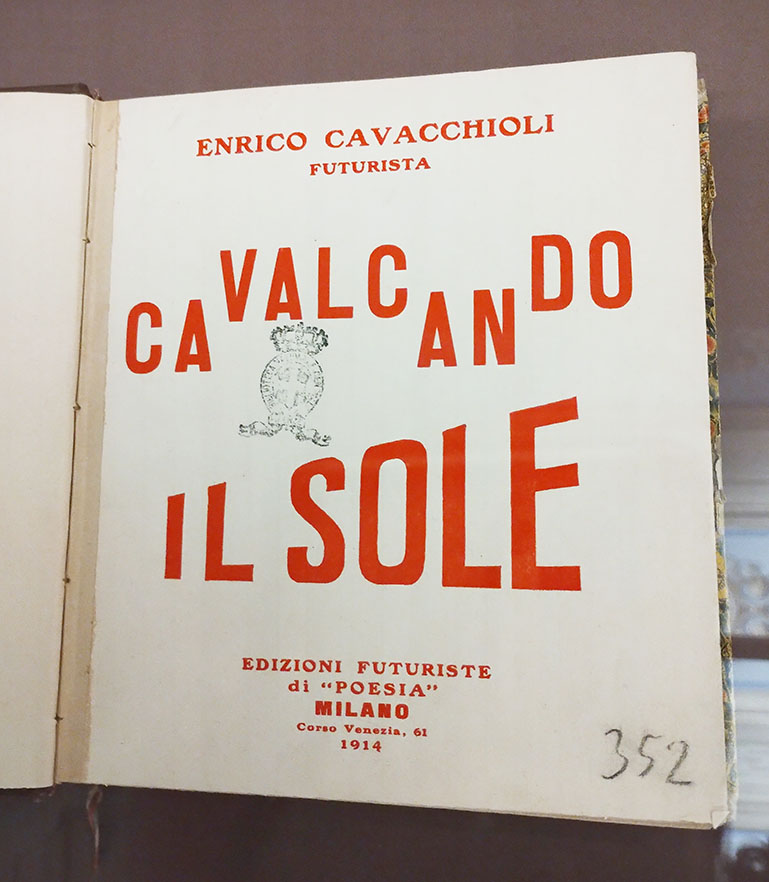

Also worth noting are other publications by Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia”, Pittura Scultura Futuriste (Plastic Dynamism) (1914) by Boccioni, Cabalcando il Sole (1914), by Enrico Cavacchioli, and Mascherate Futuriste. Transvestite lirici (1917) by Emilio Settimelli.

Happy with the unexpected visit, we abandoned the tour of the Italian avant-garde of the early 20th century to immerse ourselves in that other avant-garde, the humanistic of the Renaissance that emerged right there, but several centuries earlier, around the 15th century. Passionate Italians!

Note:

1. See more

2. Marinetti, recognized founder of the movement, visited Argentina twice, in 1926 (See more) and ten years later.