Everyone, this week of October seems to confirm it, is nothing more than a collection of ruins from yesterday and an excuse to produce those of tomorrow. Mute, changed places, crooked, lame, sore, useless as nightstand decorations, we humans get used to living with them, stepping on them, jumping on them, chopping them, crushing them or ignoring them without talking to them or seeing them. Layers and layers, sediments of other lives, that the wells, the excavations, the plows, the constructions and the pumps bring to light to throw them into the work and days of each other. It is also true: this abundance has generated innumerable professions and customs, as well as knowledge and the certainty of the weight of the centuries that, from the basement or the roof, mockingly contemplate us while they wait for our turn.

Certain moments in history have been particularly fond of generating them, others of preserving them with invented techniques to disguise the direction and smell of things. The 19th century, for example, was illustrious in the production of garbage and its transformation into Sunday enjoyment. I have already written about it and I will continue writing: I do not get tired of my fillers or my crusades lacking the Holy Land; Surely, one day, I will finish the promised book on the emergence of archeology and paleontology at the time of the discovery of the value of garbage. But now, here, it is the turn of some poor elephants whose relics were left on the side of the roads that saw them pass by alive, in a caravan, with their own name, cheered and crowned with feathers. Are two. First, Miss D'Jeck.

Elizabeth Gordon, the daughter of the Reverend William Buckland (1784-1856), the professor of geology at Oxford University, remembers that her father had a habit of writing his sermons on slips of paper. But Buckland also composed his great treatises in the same way: among the few documents that survive him, there is a newspaper clipping without date or provenance, of just four lines preceded by another two, handwritten, a comment on the futility of things, of causes and history. Buckland's lyrics read:

Elephant

A puzzle for geologists, for when, in the future, the Atlantic emerges and forms a new continent.

A prelude to the news that Mademoiselle D'Jeck, the famous elephant of the Adelphi, had been thrown overboard during a storm that affected the ship that was transporting her to America. A tiny message about a burly animal sacrificed to save humans; a fact that, in Buckland's vision, would create an irregularity in the geological record that was currently being formed and that would be impossible to understand without resorting to a contingency that no geologist could guess. It seemed a mockery of efforts to explain marine deposits on land and terrestrial deposits in the sea. The state of things was not permanent, but at some point the Atlantic could emerge and transform into dry land. But it was also a warning about the conclusions that were being drawn in the geology of the time, so abundant in finds of elephants and other African and Asian animals in unexpected territories, evidence of the forces that had shaped the land and seas of the past.

But the news is also an irregularity: since the elephant in question was famous, there are plays in her honor, books, biographies that tell another purpose, revealing that her bones are not at the bottom of the sea since she was shot in Geneva, Switzerland. , in 1837.

The Lady had arrived in London in 1806, from India or Ceylon, a member of Mr. Thomas Atkins' traveling menagerie. Two years later she received the stage name Ella and was sold to the menagerie with whom she traveled around England until 1814, when she arrived in Bordeaux, where she wounded the mahout who had raised her. In 1822 and in Marseille, she hurt her owner: she was sold and taken to Berlin, where she continued to attack her caretakers. In 1829, she appeared with great success in the Paris Olympic circus, starring in the play "The Elephant of the King of Siam." At the end of the summer, the owner of the Adelphi Theater in London hired her for the winter season. But before she hurt the owner of the circus and fractured the skull of Alberto, her “mahout.” She was introduced in Bath, Bristol, Dublin, Plymouth, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, York, Nottingham and London, the territory of her prehistoric ancestors. There she broke the arm of one, wounded and killed two others, and nailed the third of hers in the skull with her defense. It was at that moment when they decided to ship her to America where she would perform in New York - she did so in eighteen performances at the Bowery Theater -, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk and Richmond. The news of her Atlantic sacrifice, perhaps, dates back to this trip or perhaps it was a ruse to appease the voices of those who called for her head. In fact, she returned to London after 9 months on tour only to lose her fangs, sawed off by her owner. The spectacle was offered in France: in Bordeaux, already toothless, she managed to kill her old mahout.

Bowery Theater, New York. 1826. Photography. Courtesy: New York Public Library.

The Franconi circus presented it in Paris and from there it continued with Alfred Pitrus' merry-go-round. In Troyes, she hurt a clown. She worked in Rouen and traveled to Belgium, where, in Mechelen, she injured two employees, attacks that were repeated in Lille and Doucheray. Fed up, her owners sold her for a parade at the military school in Metz at the carnival of 1836. She then continued towards the Rhine, Prussia, Bavaria, to return to France via Strasbourg and Mulhouse. In Switzerland, she toured Basel, Bern and Lausanne. Her life would end on June 20, 1837, when she was shot after an incident with a spectator. As everything is useful and it gives money, in 1839, its skin was for sale in the house of Deyrolle, a naturalist and preparer from Paris, who offered it to Barthélemy Dumortier, botanist, director and founder of the Natural History Museum of Tournai. . Miss D'Jeck would return to Belgium in 1839, the first embalmed elephant exhibited in that city. It was assembled in 1841 by Jean-Baptiste Loucheur, the museum's preparer, thanks to an oak mannequin built by Mr. Vandekerchove de Kain, the intervention of Lefebvre, a local artist, and the shoemaker Louis Ménart, who would end up sewing the skin to the wooden structure for 29 francs and 50 centimes. The operation would cost a total of 741 francs and 48 cents. Miss D'Jeck, in that state, survived both world wars and in 2018 was recognized by the Federation of Wallonia-Brussels as part of its federal heritage. The whereabouts of her bones are unknown, as is where she got the teeth that she now displays for the amusement of the children who come to visit her.

Mr. Fritz, on the other hand, had a more stable life but that did not help him avoid a similar end: he would die in June 1902, strangled in the streets of Tours, on the banks of the Loire. . He was an Asian elephant, born in the 1820s and acquired by the Hagenbeck brothers, the Hamburger company dedicated to the animal trade, one of the main suppliers of the Barnum circus, the American company that came and went from one continent to another, where Fritz, beginning in 1873, was trained and where he performed for the rest of his life. Until that fateful summer of 1902, when in a parade through the city of Tours, the elephant, for unknown reasons, went crazy and became uncontrollable. It was his death sentence: the director ordered him to be restrained with ropes and chains, a death that would take more than three hours. He also had another idea: he decided to give the corpse to the city that had seen him dying.

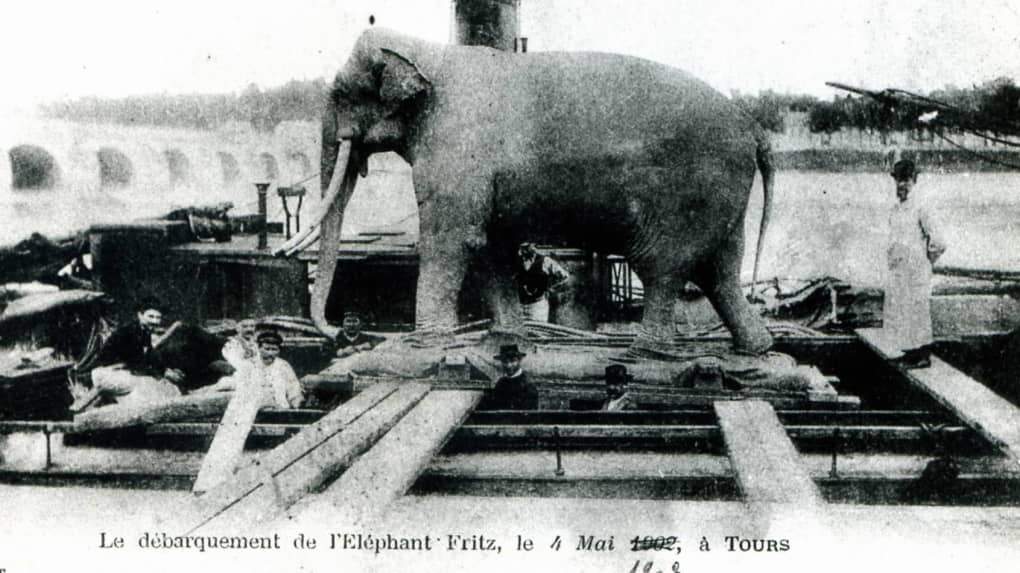

Since it was hot and things rot quickly at those temperatures, he urgently called a skinner and a leather tanner from the region to prepare the skeleton and skin and send it to a resident expert in the assembly of skeletons and animals. in the city of Nantes. The skeleton and the “embalmed” elephant returned to Tours in better condition than when Fritz was traveling alive: they came by boat along the Loire, docking in May 1903. After a reception and a small parade, they were transported and displayed in the Museum of Natural History, then located on the banks of the river. The photograph of his arrival in Tours soon became one of the many postcards published by Neurdein Hermanos (1863-1918), one of the photographic companies that fixed the emblematic sites of French tourism, sending operators to tour the country to capture the news. and the shots that are repeated to this day.

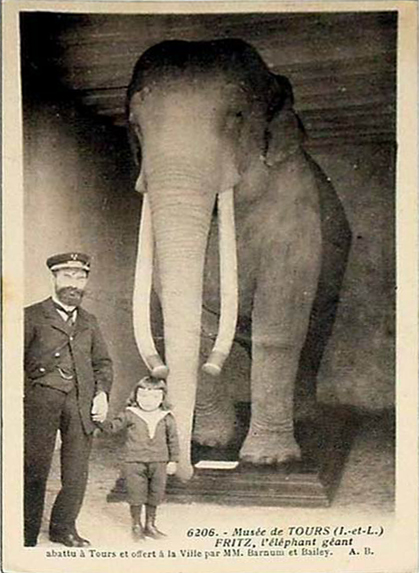

Once the euphoria of its arrival had passed, the skeleton was placed in a room on the second floor of the museum while its skin presided over the entrance. In 1910, due to lack of space, the taxidermied specimen was moved to the stables in the garden of the Museum of Fine Arts, the former episcopal residence located next to the cathedral, in another neighborhood of Tours. A move, in fact, providential that took him away from his bones, but saved him from the fire that affected the museum and destroyed it in June 1940, during the bombings and combats of the Second World War that devastated the entire area near the bridges of the Loire.

“Fritz” was restored in the late 1970s and, since 1977, a glass box has protected it from the elements and the handling of visitors who come to admire it, dead, still, in silence. From there, his glass eyes can gaze at the branches of the Lebanese cedar planted in 1804 in the center of the palatial courtyard. Huge, supported, like him, with wooden crutches. So that they do not fall and remind us that, in the end, everything hangs by a thread.

Editor's note: Miss D'Jeck is one of the protagonists of “Desubicados” (Beatriz Viterbo, 2022), the latest book by Irina Podgorny.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades