Much has been written and is being written about the relationship between Argentine science and politics in the 1880s, celebrating an alliance that -for better or worse- would have laid the foundations for the national future. In those years, two scientific commissions accompanied the military expeditions sent by the Ministry of War: one to the Río Negro (1879), the other to the southern Chaco (1884 / 1885). Few, on the other hand, have dealt with the ephemeral nature of these associations resulting more from a favor than from the design of the country's future. Without mentioning the conflicts that these aroused among the group of scientists who were marginalized from them, when there they had seen a possibility of ingratiating themselves, of consolidating their position, of earning some extra money or of traveling and making collections with resources parallel to those destined for the army.

This note, which is based on a chapter of my book "Florentino Ameghino & Hermanos", refers to that and how these problems were resolved in the press, the stage of the negotiations, where each newspaper acted supporting one or the other. . And in particular it refers to the expedition to Chaco, an episode always celebrated in Ameghino's life of which, curiously, no results survive. This note reveals why.

Irina Podgorny's book, published in 2021 by Edhasa.

Already in October 1884, clashes had begun between those summoned to accompany the Minister of War in the Chaco War. It is that, aside from the military Expedition, it had been decided that the scientific commission would leave directed by an unknown person: a certain Leopoldo Arnaud, with a remuneration of 350 pesos per month plus 2 pesos per day for travel expenses. He would be accompanied by the hydrographic engineer A. Rosenthal earning 250 pesos; the collecting geologist Florentino Ameghino, at 200 a month and the geological preparers T. Schulz, and botanist K. Galander, with 100 each, as well as C. Rodríguez Lubary and J. Haver, zoological and agronomist assistant collectors.

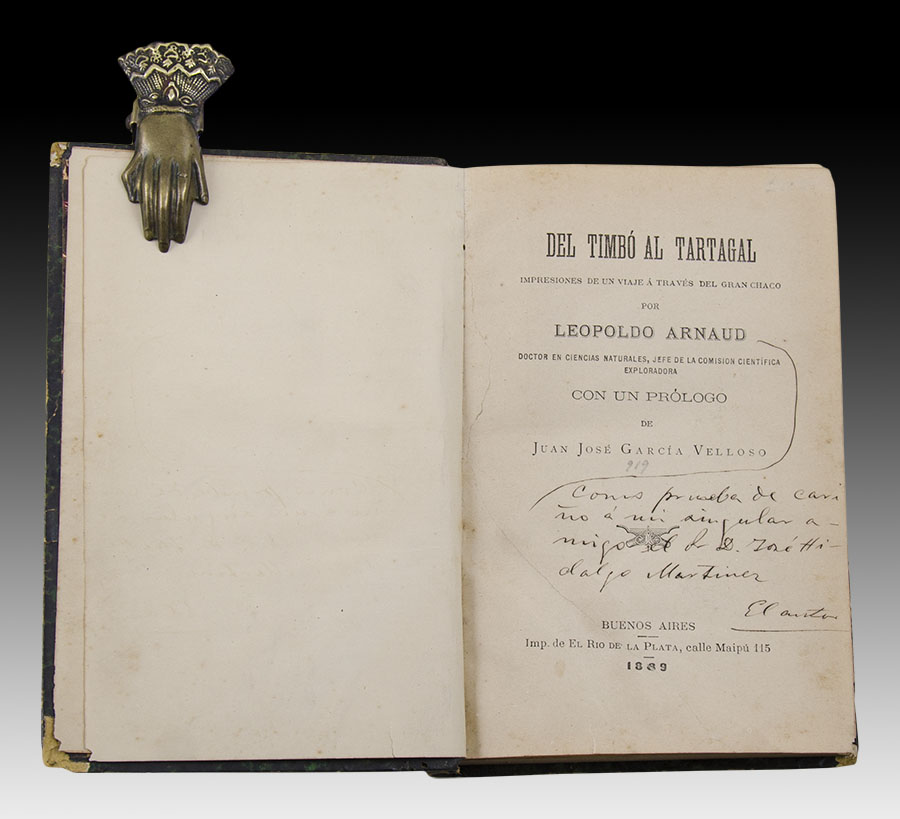

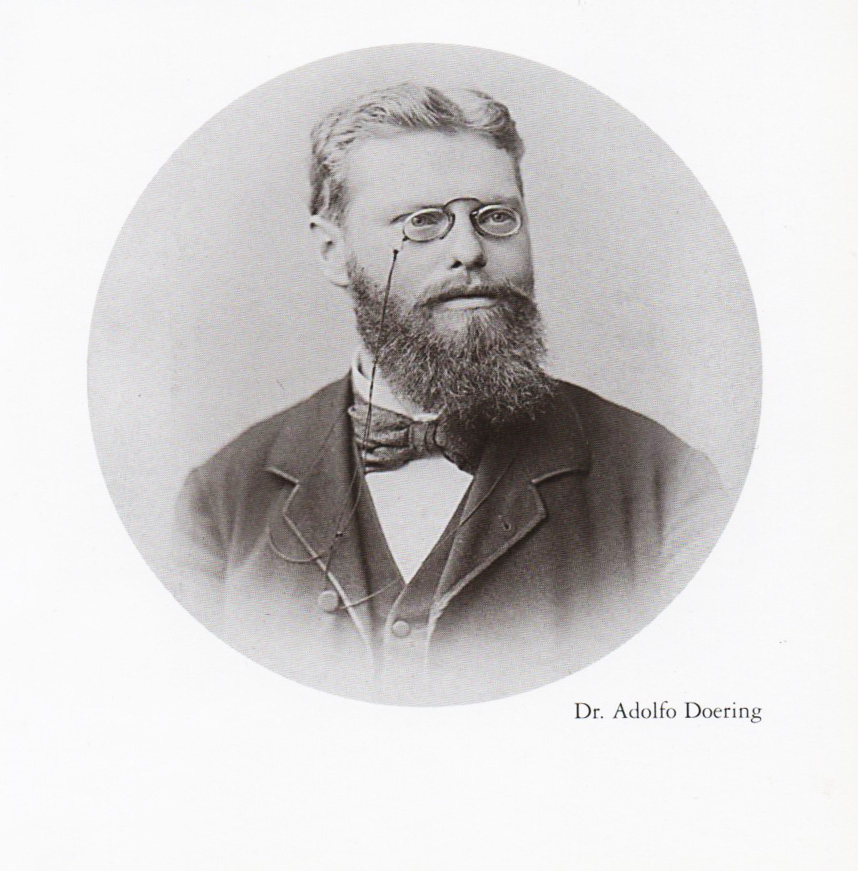

The newspaper La Crónica came out to defend the commission from which, at the last moment, the names of the engineer and the geologist had been dropped. But the biggest problem lay in the young Arnaud, who, to the delight of La Unión and El Diario, presented himself as "Stanley's partner", the famous expeditionary of Welsh origin who had entered the African continent, first encountering Dr. Livingston in 1871 and later, exploring the Congo River, between 1874 and 1877. Arnaud was barely 25 years old, at what age had he accompanied him? La Crónica, however, defended him: Arnaud had proven his extensive scientific knowledge as a professor of Natural History at the main official school in Havana, where he came from, he assured in his pages. Arnaud himself, in later publications, would mention his Cuban life, referring to the nostalgia he felt in the Chaco when comparing the nature that surrounded him with the women, the music, the landscape, the mills, the slaves and the palm trees of the island. Adolfo Doering, professor at the Academy of Sciences of Córdoba and in charge of the Scientific Commission that had accompanied Julio A. Roca to the Negro River but displaced from the Chaco headquarters, considered him "an ignorant Galician" and made it known to everyone. the media.

La Crónica, for unknown reasons or perhaps for not earning the enmity of Minister Benjamín Victorica – with whom the setting up of another commission was being negotiated – actually defended the indefensible. The son of Leonardo and Carmen Orge, a family originally from Galicia, Arnaud would have been born around 1860. His father and his uncle Leopoldo were doctors; the latter, who also had a doctorate in pharmacy and letters, had moved to his wife's properties in Cuba. His other uncle, Colonel Hipólito Arnaud, had been governor of Cienfuegos. Perhaps Leopoldo traveled to the Caribbean following his family, placed in the administration of the overseas territory.

Arnaud's attackers and defenders from Buenos Aires did not consider that, in reality, he could be the clerk of the same name, a native of Valladolid, single, of legal age, employed in the Cuban city of Matanzas and who, in 1880, had been laid off. , accused of falsifying receipts and checkbooks of the administration, in whose name he collected, keeping the proceeds. The fraud for more than 45 thousand gold pesos, was discovered by the indefatigable Canarian inspector José Trujillo, grandfather of the Dominican Generalissimo Rafael Leónidas. Our Arnaud, after the trip to Chaco, continued in Peru and Madrid to finally settle in the United States. He died in New York in 1931, where he had married Fortunée Marie-Louise Zacharié, mother of Leonardo and Leopold, later head of the architecture department at Columbia University. Arnaud's life is, as we shall see, a comforting story of impostures crowned by success and self-confidence.

He was not the first trickster to arrive in Buenos Aires with the desire to become an explorer hired by the government who, here, in Bolivia or Colombia, easily fell into the nets of the fraudulent. Arnaud managed -in the north and south of Ecuador and on both sides of the ocean- to convince his children, who was a doctor of natural sciences, to the end of his days. Counterfeiting was one of the great companies of the second half of the 19th century, linked to the expansion of the typographic industry, the value of titles and the growing technical capacity of individuals promoted by advertising and printing. Quite likely Arnaud's fine manners and experience in tropical climates played in Arnaud's favour, apart from the occasional role played by his own hands: Cuba and the Congo must have been quite similar to the inhospitable southern Chaco. At least, to the ears of the Ministry of War.

The Argentines were not so bothered by his past as that, in July 1884, fifteen days after arriving in the country, presented through the head of the Department of Military Engineers to the Minister of War and Navy, he was appointed president of the Scientific Commission and Head of his expeditionary column, which, unrelated to the military expedition, had to travel the territory, studying and verifying "the special conditions that occurred in the unknown extension" in terms of topography, hydrography, geology, fauna and flora etc.

His journalistic defender, La Crónica, asked that he be judged upon his return, when evaluating the production of this unknown young man, whose self-esteem was equally hurt by the newspapers and the “passionate appreciations of some adversaries or envious by condition. ” Arnaud, later, would celebrate: the same ones who cast "the public with doubts about success, the same circles that criticized the Government for putting a mission as important as it was delicate in unknown hands", ended up admitting their mistake to turn their criticism into praise for the results of the several months of the expedition. To such an extent that when Arnaud passed through Madrid in 1889 to visit Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, he presented himself as delegate of the Argentine Republic and scientific correspondent for El Diario, the newspaper that had most harshly questioned him in Buenos Aires, and where two years before had published the observations on the oil in Laguna La Brea in Jujuy. However, in the works that he left to don Marcelino, he apologized for the meager results, appealing to accidental losses and poor personnel. Like Ameghino in Phylogeny, Arnaud warned “those who read this book should not expect to find literary beauties in it.”

Arnaud and the Scientific Commission had to submit to the instructions of September 1884: determine the quality of the lands of the southern Chaco from the geological and mineralogical point of view, both in the scientific sense and in that of industrial application, making known the pastures and the agricultural genre to which they could dedicate themselves. They also had to classify the minerals and the direct utility that they could bring to the industry and, secondly, attend to paleontological studies when the circumstances were favourable, conserving the fossils that could be acquired, leaving the investigation for later. Flora and fauna were third and fourth on the list of tasks: the collection of specimens had to be presented to the State prepared, classified and arranged according to science. Finally, he had to deal with "geographical-political studies of the found tribes and the conservation of all those objects that, apart from offering interest to archaeological study, offer it to public curiosity". Two diaries were to be kept: one with the day's studies and observations, the other with travel impressions. If someone left on his own, faced with the possibility of not returning, he had to leave the collections in the camp at the chief's disposal. In Buenos Aires, the General Staff would provide a place to deposit them; once studied, they would be placed at the disposal of the Ministry.

Given the casualties and resignations, Arnaud's commission was made up of the engineer Emilio Donegani and the collectors Carlos Rodríguez Lubary (zoology) -Holmberg's cousin-, Alejandro Edelmann (botany) and, in geology, Toribio Ortiz, Pedro Scalabrini's brother-in-law. , uncle of the much talked about Scalabrini Ortiz. They were joined by the agronomist Juan Hawer. The lack of trainers -said Arnaud- announced the failure of a task to be carried out at temperatures that, from one day to the next, caused the decomposition and putrefaction of things. The caravan set off together with the commission of engineers from a point called Timbó (Puerto Bermejo), with a cart driven by six oxen, a dozen loaded mules and another twenty oxen. The driver was an Indian of the Carayá; the guide, an old Toba, and a linguist acted as interpreter since none of these spoke a single word of “Christian”.

Arnaud would later write that, in the itinerary, the fauna and flora were not very varied. As for the fauna, Holmberg's cousin, while he was on the Commission, collected 800 insects, 500 arachnids and 25 reptiles, but Arnaud left his classification “for another more opportune occasion”. The mammals –according to Arnaud- rotted with the rains; Of the birds, 16 survived. Instead, he had 816 pressed plants and the promise of making the resources of the forests known. At the end of November 1884, Ortiz and Rodríguez Lubary were removed from the Commission by means of a summary, given that their behavior –in the words of Arnaud- was not satisfactory. Misunderstanding reigned among them.

“Son, dedicate yourself to your profession”

In that same month of November, Adolfo Doering and Eduardo Holmberg, the doctor and naturalist, embarked on a controversy that the newspapers of Buenos Aires aired in a manner close to that of a feuilleton and that would reach its climax in February 1885. In a series of letters titled “Holmberg vs. Doering” and “Doering vs. Holmberg” brought to light the turbulent and intriguing character of the Cordovan professor, all as a result of Holmberg's appointment in the direction of the (second) scientific expedition to Chaco.

Doering threatened: he would not let Ameghino or Kurtz go under the direction of a brat with pretensions of being a Great Mogul, a nickname that probably referred to the Italian charlatan Guido Bennati, Commander of the Order with that name who at that time displayed his Museum South American scientist a few meters from the National Museum directed by Hermann Burmeister. Holmberg was bothered by the suspicion that he had been the one who had introduced Mr. Arnaud to the Minister of War, when the first time he had heard his name had been in the lobby of the National Government House, in Colonel Olascoaga's office, who, after talking for a moment, asked him to come back two days later because now he wanted to interview Arnaud, a very educated young man, a companion of the famous explorer of Africa.

Adolfo Doering was present as the supposed person in charge of the future Commission, that was the agreement. But by the next day, Arnaud had replaced Doering as chief. Following orders, Holmberg returned to Olascoaga to introduce him to his cousin Carlos Rodríguez Lubary, a companion from other trips, who, in the Chaco, would take care of the articulated animals (arthropods). Regardless of whether Arnaud was educated or ignorant, of his bold or brave character, Holmberg did not want to interfere. Neither find out if Olascoaga had done wrong or right. On the other hand, it was true that he had promoted his cousin, who now, at the time of the fight, was entertaining himself in the Chaco collecting mosquitoes, spiders, and ticks. He had also prepared boxes and condoms, in addition to modifying instruments to make the collections: the list of objects given to Arnaud consisted of 25 items with 10 drawers, the largest over a meter long and the others successively smaller, in such a way that , by carrying them one inside the other, they will occupy the smallest possible bulk. Holmberg insisted: the mere presence of Arnaud did not determine the scientific failure of the expedition, guaranteed by his companions. Mr. Arnaud in the Chaco was not a scholar, but an individual, the head of an expedition that was to gather Natural History collections that would later be placed in competent hands.

In February 1885 -while Arnaud was traveling to the north- in order to continue studies related to the natural history of the Chaco territories and immediate regions, in accordance with the law of September 15, 1884 and taking advantage of the offers of several members of the National Academy of Sciences, the Ministry of the Navy announced that professors Holmberg -director of the expedition- and Florentino Ameghino would be commissioned to proceed to complete the studies and works on the physical constitution of the area in the way they believed most convenient . The commission would be completed with the assistants Constantino Solari, Federico Schulz, Carlos Goloner and Carlos Ameghino, who were assigned a monthly salary of 100 pesos. At the end of their studies, teachers had to submit a detailed report of the observations and studies carried out. "The truth is that the situation of the Treasury and the current times invite us to make these and other expenses" -said the newspapers- indicating, thereby, that public money, as well as in times of crisis, should not be wasted on these luxuries, now, they were used to invest in as many commissions as necessary.

With the publication of that news in the carnival of 1885, Troy burned. While Doering and Holmberg were fighting and Ameghino was caught up in the controversy, Arnaud, in Chaco Salta, believed he had been blinded by the fireworks that the engineer Donegani had experienced on the occasion. El Diario, which had previously denounced Arnaud, reconstructed and published a discussion between Holmberg and Adolfo Doering on the corner of Florida and Piedad, in the heart of Buenos Aires. Doering vociferated that he would be decidedly opposed to such an expedition, because it was convenient for the Faculty of Córdoba, preventing his professors from being part of it. The Faculty, influenced by him, would resist any resolution of the Minister of Public Instruction, since his decisions were superior to his determinations, he assured. Holmberg replied that it was not "turkey", that the decree was signed by the President of the Republic and the Minister of War, that the former was interested in the expedition being made and that he would never have imagined the opposition of the Faculty to the Government. National, on whom it depended. A grainy fire revealed previous disagreements.

"-You. he was able to use his influence so that Arnaud was left without the best assistants, but he is wrong if he thinks that the same thing will happen to me.

-He will see how it happens.

-But now they are teachers, not assistants.

-Kurtz and Ameghino will not go because we will make war on them if they do.

-Take the test.

-Then the assistants won't go.

-Don't go.

-And in any case no serious man should accompany Arnaud.

"But at least any well-educated man answers three telegrams from a minister, if only to excuse himself." And here it is common that it was you who told him not to answer.

-You don't care what happened to Arnaud, he's an ignorant fraud and you told the minister before embarking.

-None of that matters to you, but it does matter to me that you are writing to stupid people out there, as happened last time with Eduardo Aguirre, when he published that the "national government" was doing something stupid by naming him for I don't know what Artesian Wells Commission.

-I was the one who wrote it- and what about that?

-Nothing, absolutely, but that is the behavior that you observe when there is money interest involved.

And these words were followed by a hurricane of German sounds, incomprehensible even to those who emitted them, but accompanied by furious looks that quite clearly expressed the state of mind of both interlocutors. Doering's glasses capered, Holmberg's top hat swore. The former strode away, while Holmberg stood looking at him with folded arms. "It seems that the cats that were locked up are coming out!" - said El Diario.

Doering indignantly ascribed that column to Holmberg's brat. The dispute would then continue between the young man "Eduardito" and "Adolfito, the most estimable of the blonds who dive into any puddle in which they can serve as a swimming pool for a petit-crevé", aggressions in carnival with "discharges and outbursts of a joyous madness scientific."

The Council of the University of Córdoba and several newspapers in that city had long been opposed to the departure of professors from the Faculty of Physical-Mathematical Sciences during the first part of the school year. The number of students had increased and a stricter and more continuous service was demanded than in other times. The departure of the professors could be verified without hindrance in the second half of the year, as soon as the main course had concluded, beginning with the repetitions. On the other hand, leaving at the beginning of the course, the rest was rendered useless.

Holmberg, in revenge, treated him like a decadent dandy: “He is no longer young, he is no longer a child, he is no longer an Adolfito; he is a blond scholar who borders on forty as he who writes this borders on thirty-three…” In the words of Holmberg, this German – basically a provincial from Lower Saxony, alien to the customs of the so-called Buenos Aires aristocracy – had adopted the credentials of the good life: he went to the Uruguayan resort of Los Pocitos to swim and fish for catfish, because some made him believe that it was fashionable to fish at four in the morning. The scientific Doering –secure, patient, well prepared- coexisted with the social commerce, restless, turbulent, devoting “a part of his time to the noble and prudent task of improving the representation of his pocket, tirelessly dedicated to pursuing high positions public.” Holmberg brought up those dark dealings, he recalled the delay in delivering the geological report of the Expedition to the Negro River. We are in 1885 and the work is not finished. The Chaco Expedition led by Doering is announced. Holmberg offers the Ministry his services to “thus somewhat temper the effects of Adolfito's intriguing spirit. Doering makes I don't know what mess and resigns. Instead he names himself Arnaud”. Perhaps the minister, fed up with these comings and goings, has opted for the latter, someone new who, even if he did not comply, would not be a novelty or be so important.

Doering, before resigning, had informed him that the ministry had formed a river commission. Unexpected events delay his departure. Arnaud, in Chaco "has the inconceivable audacity" to blame his failure on Holmberg. Doering - Holmberg summed up - was nothing more than a drone who had come to imagine that "our country was a country of barbarians in which we must always bend the knee to an imported knowledge that insults us and cowards who use anonymous to offend to people who yesterday were treated as competent and then as stupid, just because it suited the anguish of the pocket.” Doering retorted these "caprioles of excited fantasy", declaring that he had received nothing in payment for the Report to the Black River; "Which is not strange, because he has not finished it" - countered Holmberg who had corrected his idiomatic nonsense, a sore where Holmberg crushed with pleasure. He was surprised at how Doering had forgotten the good times he had spent in order to “find out for each other what he would have wanted to say with such or such words, phrases and paragraphs that more than once tortured his caletre”. His father, reading this vaudeville, advised him not to abandon his medical studies: "Stop this, son, and dedicate yourself to your profession."

Doering, in Holmberg's description, appeared as an ambitious man, pending "praise societies and mutual hype", capable of betraying his allies, harassing the people of the National Government. He traveled to Buenos Aires for no purpose and it was within the framework of these trips that he began to transform his Byronic hair. Holmberg recognized Doering's geological and malacological sophistication, that very few could judge. The discussion was not scientific, as some claimed.

The river excursion

In March, before leaving and embarking on the "Río Uruguay", Holmberg left his post as editor of La Crónica, a newspaper of the Gutiérrez brothers that he had helped to found. The trip to Chaco seemed like a definitive goodbye. The members of the commission were on their way to latitudes where the rigors of the climate were torture; danger and suffering, a reality. They abandoned the sweetness of home, the comforts and flattery of civilization, driven by vocation, love of science and Argentine progress. Everyone knew that the first expedition had been unfortunately organized, “the Ministry acting as we understand, in the rush of the last moments, by light reports or without serious basis regarding the competence of the people to whom it was entrusted. Our statesmen have believed, and rightly so, that the sacrifices made to pay for astronomical observatories, scientific academies and foreign scholars brought to the direction of public museums fell to the honor of the country, because the works of Burmeister and Gould, of Latzina , of Lorentz, of Doering, showed Europe and the world that the nation that financed them, applauded them and promoted them was a nation whose intellectual and civilized level was already high and that knew how to put its grain of sand in the common work of the peoples that science is, the heritage of all humanity. Today that there are Argentines already occupying distinguished positions in the scientific world and whom we see quoted with appreciation in European works, the government should congratulate itself with double reason for their efforts to advance higher education in the republic, and not believe that perform work of little significance in the above sense, when he sends compatriots such as Holmberg and Ameghino to study areas unexplored by science, whose research will circulate tomorrow arousing interest and curiosity in the American and European cultural world.”

On March 15, 1885, ten days before Arnaud terminated his mission in the city of Salta, the commission chaired by Holmberg arrived in Formosa. Those poets and sages who loved, admired, investigated and understood nature, those workers of progress, those patriots, immediately set out on the campaign, hunting, fishing, scanning the ground, seeking and searching for every living thing and collecting all kinds of weeds. Among those, a three-inch fish that seemed to be a lepidosiren. In reality, they did not know what to do: they were stranded by the delay of the commander of the little scout steamer. For this reason, in order to take advantage of the time, Kurtz and Ameghino traveled around Paraguay, at their expense and assisted by Carlos, an understanding assistant to his brother, and young Solari, a tireless fisherman. They were accompanied by Léontine, Florentino's wife. In Paraguay they met the Bommert couple who began efforts to establish a museum in Asunción so that the excavations would be made for the benefit of the nation. This trip of the Argentines had awakened the possibility of living from the sale of animals, fossils and minerals of the country. Bommert -for a monthly fee- would change his trade, help Ameghino and transform his carpentry into a natural history laboratory that could later have a branch in Buenos Aires. He asked her for tweezers and boxes to collect beetles, metal wire to mount birds, glass vessels to preserve animals, a magnifying glass, a compass, and manuals for dissection and taxidermy. The wife would also get involved.

This wait, beyond the possible deals that were beginning to be hatched, worried them: it compromised the success of the mission. La Nación reported: “The bureaucratic hindrances of the Ministry are the hindrance of a disinterested company, destined to raise the name of the country higher in the scientific world. The best intentions, the proven competence, the most determined zeal, animated by the sacred fire of the vocation, cannot fight against the clerical inertia and are in part sterilized. Meanwhile, another cousin of Holmberg, the sculptor Correa Morales, gave the artistic note: he had found several plastic clays, recognized by Ameghino, with which he had made some sketches, also taking photographic views of the virgin forest of Formosa. In the end, if it had not been for the cooperation of the Government of Formosa, in charge of the Englishman Ignacio Hamilton Fotheringham, they would not have been able to even make slight excursions by water and land. A paradox arose: “this time that the National Government has had the wisdom to gather competent men for an object so worthy of attention, it would be sensible that due to indolence and carelessness they left the work incomplete”. As expected, the dilemma would be resolved on the obvious side: nothing happened and the river expedition came to nothing.

In mid-May 1885, Holmberg, Ameghino, and Kurtz were returning from the Chaco, where they had observed nature as poets and scholars. The press, with the exception of La Crónica, barely greeted his arrival.

Ten days later, Arnaud left Salta, where he had convalesced from liver disease. On June 5, he arrived in Buenos Aires. Perhaps with some luck for everyone, indifference reigned in the city in the face of everything that was not electoral matters and the fights with the former Nuncio. Victorica, in those same days, resigned from the ministry in disagreement with the presidential candidacy of Juárez Celman. The shame of failure was diluted in the avalanche of those disputes.

The expeditionaries led by Holmberg brought 7 to 8 thousand animals, 4 to 5 thousand plants and several fossils and soil samples intended to give "complete knowledge of the region traveled and to serve as a basis for accurate judgments of the role assigned to it in the multiple evolution of our wealth.” Observations were not lacking either. Studying this material, he would proceed to write a work that would require at least a year and a half of intense work. The text was largely written from the diary and general observations, as well as from the sections referring to flora, paleontology and fauna. However –they highlighted- the results had not been as important as expected due to the null elements of mobility. So much mocking of Doering, the reports of this commission would not be published either. Arnaud, on the other hand, built his name associated with the Chaco: in 1889 he published “Del Timbó al Tartagal”, educated his children in France and lived a comfortable existence in the United States. Today, still, there are those who read it despite the fact that historiography covered his name with the silence of shame.

Note:

(*): Adaptation of his book “Florentino Ameghino y Hermanos. Unlimited Argentine Paleontology Company” (Edhasa, Buenos Aires, 2021), especially for Hilario.