It is known that the denomination “pampas” (or better “lelfunches”, as I have explained on other occasions), applied to indigenous people, can only be accepted as a geographical value that groups different biases. They have not been well defined until now, but there is no doubt that there has been a variation of large sets that have followed one another and superimposed through space and time. Consequently, when dealing with fabrics from Azulwe speak of the "pampas" Indians, we limit ourselves to considering as such those who in our country come from that territorial occupation or reoccupation of which some authors speak and were, later, evicted or assimilated by the penetration of the national domain in the same territory.

It follows from this that the study of tissues from Azul does not mean the consideration of a special and genuinely local type, but the examination of a generalized way in an entire breed, despite the fact that some characteristics are alien to the latter. And, therefore, the reader should not be surprised that we frequently deal with the fabrics made in the same or previous era in the Chilean places of Mapuche residence.

Little was known about the pampas fabrics of Azul when Bartolomé J. Ronco presented an initial characterization of the main material expressions of that culture in four photographs that he published in No. 5 of «Azul. Magazine of sciences and letters» (year 1930), without accompanying text. And to this were added the pieces of his collection that he donated to the Ethnographic Museum of Azul, inaugurated in 1945, whose purpose is to exhibit the objects within a cultural context, rescuing all the values associated with them and reconstructing the culture of the peoples represented. [1].

Researchers prepared by the specialty of their knowledge for a qualified observation, give correct news about the pampas textile industry. Such is the case of Carlos Dellepiane Cálcena who, in 1960, published his field work carried out in Villa Fidelidad (Azul) in November 1957 and February 1960, in which he explained the survival of the textile technique used by a folk community of pampa origin [2].

A context picture, with more news, I released in mid-1978, as a result of an interview I conducted with Ercilia Calderón de Moreira - daughter of Pascuala Calderón and mother of Ercilia Moreira de Cestac - in her house in Villa Fidelidad during the hot December 1977 [3].

Ponchos and pampas girdles in stories of chroniclers and travelers.

The reconstruction of this theme has been based and still is based mainly on the news that emerges from written and printed sources of varied antiquity, which we owe to chroniclers, travellers, etc.

The few chronicles of the 18th century and the stories of the travelers who knew Azul and the nearby tolderías in the decades after the founding of the Fuerte del Arroyo Azul (1832) and in the years in that the exchange with the indigenous was greater.

Chroniclers and travelers generally confine themselves to the simple mention of the industry – the looms – in its relationship with the clothing of the indigenous and the traffic with the settlers of the border. But they do not provide illustrative details that make it possible to establish the procedures and various aspects of this industry and to appreciate the quality of its results. The fabrics, whatever their typicity, are the expression of a meek and monotonous task, and are attractive only to the small number of those who notice in them elements of research that are more transcendental than their quality or unusual aspects. Of those who toured the province of Buenos Aires, we can only find out that the indigenous people wove ponchos, blankets, jargons, and belts. That is what the references, in the eighteenth century, of the PP. Jesuit Thomas Falkner [4]. and José Sánchez Labrador [5], since they do not provide any useful reference on the preparation itself, instruments used, decorative themes, dye materials and everything that could serve for a more in-depth knowledge of indigenous technique and skill. The same thing happens in the first half of the 19th century with Alcides D'Orbigny [6], Francisco Javier Muñiz [7], William Mac Cann and Federico Barbará. These last two were in Tapalqué, the first in 1847 [8] and the second in that same year and the next in 1848 as a dependent of a business house [9] but they omit any comment about the looms and the active trade that these fabrics gave rise to and necessarily perceived Barbara.

Leaving our country, the news that various authors gave about Mapuche looms, the immediate origin of the pampas and the true source of production of many of the ponchos, matras and girdles that were trafficked as of blue clothing.

Trade of pampas textiles.

If there is no certain data about the oldest date regarding the making of pampas ponchos, art. 2° of the treaty celebrated in 1742 by Governor Miguel de Salcedo with the Pampas caciques, reveals to us that they agreed that Cacique Bravo and other friendly caciques would set up their tolderías in the mountains of Tandil and Cayrú (Olavarría), where they would celebrate «the fair of los ponchos”, in which the textiles would be marketed, when the time came for it [10].

Mac Cann observed when he passed through Dolores, in 1847, and as a result of an encounter with the Tapalqué Indians, that they obtained up to fifteen or twenty mares for each poncho. [11]

Víctor Martin de Moussy, for his part, dealing with the indigenous industries in relation to the different partialities offered by the Argentine geographical extension, affirms that the Indians of the south, especially those of the Mapuche race, were infinitely more industrious than those of the north and concludes stating that the women of the first "dexterous and skillful, weave wool fabrics that they know how to dye with the brightest and most indelible colors, and thus make ponchos, horse blankets [slangs] and belts [sashes]", adding in final lines that some pampas had installed in the suburbs of Buenos Aires houses selling these fabrics and other clothing of the same origin, which later disappeared and were replaced by traffickers and peddlers who came to the tolderías and acquired by barter for European merchandise of low price, all products of aboriginal manufacture, giving rise to an important and active frontier trade. Said author, at the time he was writing (1863), says that two leagues from the town of Azul, with 5,000 inhabitants, the Catriel tribe, made up of 1,000 families, with 800 lancers, who spoke Spanish, was encamped and received a subsidy from the government. they raised sheep, wove ponchos and sashes, and sold the product of their industry [12].

Such meager scarcity of news, of uniform content, contrasts greatly with the copious volume of references that I have found, without delving too much into the search, in the official and private papers of the Military Command and Justice of the Peace of San Serapio Mártir del Arroyo Azul, great part of which are preserved in the Historical Archive of the Province of Buenos Aires. These documents, made up mostly of judicial inventories, balance sheets of business houses, draft censuses and proof of statistics and tax collections, leave the impression that the indigenous looms from Azul, going beyond the limits of a simple and reduced domestic task, achieved the proportions of a true industry, with great production and an extensive and sustained market.

To read some of these documents, especially the judicial inventories of business houses, is to mentally reproduce the picture that Armaignac traces in his Journey to the Pampas, written at the same time as those, and in which couples and groups of Indian women appear walking hastily through the streets of Azul, covered with their long chamales, adorned with their large tupos and their heavy silver earrings, straightened and unctuous hair and carrying with them the load of their merchandise, fabrics and manual work, to exchange them in the business houses for other foreign fabrics, or for sugar, yerba mate, alcohol, tobacco and other merchandise.

One of those inventories, carried out by order of the justice of the peace of Azul on March 10, 1862, which lists "the stock of Mr. Pedro León Martínez's business", and includes items from the warehouse, store, shoe store, hardware store, saddlery and wood. , separated into two chapters, ends with two very typical ones of the time, entitled "Frutos del País" and "Pampas Fabrics", respectively. In the latter, 22 "calamacos" ponchos are detailed, 18 "pampas blankets", 20 “plain” and “carved” wool sashes, a pair of silk garters, 4 “carved” jargons, a “braided muzzle” and 20 pairs of “foal and ostrich boleadoras”.

Another inventory like the one mentioned above, but drawn up on May 15, 1868 in the business house of Juan Duverger and his wife, Margarita Valle, in Azul, in addition to detailing the merchandise, contains its appraisal. Along with sixty imitation vicuña ponchos, valued at 42 pesos each, he mentions another twelve pampas ponchos valued at 120 pesos of the same currency each, which demonstrates the best quality of the latter.

In 1866 in the pulperías of Tandil, indigenous blankets and ponchos were offered at a rate of 220 pesos and 75 pesos, current currency, respectively, per unit [13].

At her side, Gustavo Kagel, a disciple in the trade of weaving pampas belts, watches her carefully.

A century later, in 1960, Dellepiane recorded: «We interviewed women who devotedly preserve the skill of weaving ponchos, sashes and other garments with sheep's wool. From their elders they inherited the skill they possess in handling the loom, to which they dedicate long hours of patient and painstaking work. At present, this admirable and meritorious artisan activity has greatly diminished, due to the high cost of wool and the lack of a market to place the products. The scarce production satisfies the needs of the community and isolated orders made by the inhabitants of the area».

The Weavers

The most notable azuleña weaver was Pascuala Calderón (born around 1870 and died around 1950). She ran through her veins blue blood of the princes of the Pampas and belonged to the tribe of chief Manuel Grande. She learned her trade as a child with her mother, also a weaver, and she passed away after having turned more than one hundred years old. The well-known writer Héctor Pedro Blomberg, who met her in 1934, published the following account of her: «A full sun was beating down on the miserable rancherío, in a suburb of the city of Azul. Everything seemed to sleep: the Indians, the huts, the dogs, the nearby mountains. In the vast, charred silence, only the murmur of the Callvuleufú, the blue river of the indigenous people, which gave its name to the city of the South, could be heard. The car stopped in front of a small ranch. And in another passage he adds: «In another ranch [...] Another bronze-colored old lady looked at us with the sad expression of the Indians. She was bent over a humble loom, like the Indian women of the time of Independence. And before […] One of her sons, an intelligent and beautiful pampa told us her name. – She is my mother, sir. She is called Pascuala Calderón. She is past eighty. She is always weaving, as you see her now. She makes ponchos, straps, girdles, which a man from Buenos Aires comes to buy for her. They pay him very little…- You see how poor we are, the last pampas of Catriel, those of us who owned all these fields. We are the last true Argentines, the "catrieleros" del Azul.- The Indian, Simón Calderón, smiled melancholy. The old lady kept weaving. The silence of the rancherío was profound. Do you remember the “general”, Pascuala? – The mysterious eyes of the indigenous woman rose from the loom. Her hand, wrinkled and black as a dry vine, pointed to the mud wall of the rancho. There, under the faded picture of the Virgin of Luján, she yellowed an old drawing. It was a pencil portrait of General Cipriano Catriel» [14 ].

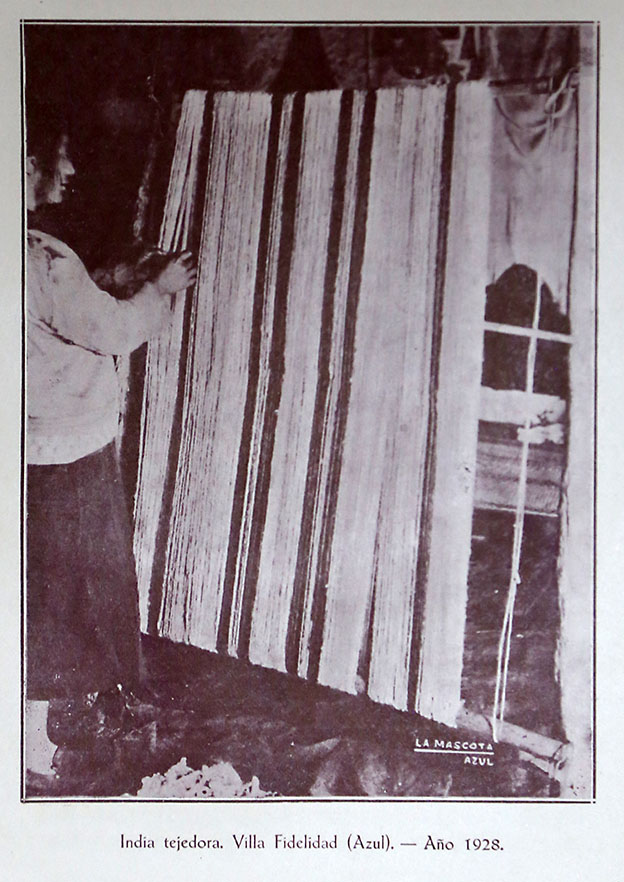

Pascuala Calderón poses in front of the photographer's camera. The serene and resolute expression on her face evidences the strength of her lineage. Azul. 1928. In Magazine of Sciences and Letters, no. 5, between ps. 192-193, Azul, Impr. Placente & Dupuy, 1930.

Faja pampa de Ercilia Cestac. Azul. Circa 1985. Fotografía: Nicolás Vega.

Pascuala Calderón taught many disciples and was the first teacher with whom the Professional School of Women in Azul, created in 1925, inaugurated its pampas weaving course, together with Isabel Oubiñas, creating a nucleus of continuing experts such as Sara A. de Sobrón , Lilia Mirande de Abot, Viviana Calderón de Vargas and Enriqueta Menetret de Mendiburu. Her granddaughter Ercilia Moreira de Cestac, born in 1925 and died on April 7, 2011, at the age of 85, continued the family tradition, which was continued by her great-great-granddaughter Verónica Cestac, born in Buenos Aires in 1977, who always lived in São Paulo ( Brazil) finally settling in Azul in the family home of Escalada 671 and died at the age of 41 in 2019.

The ponchos

The “poncho” (voice of uncertain origin), or “macuñ” (Mapuche voice), is a typical piece of Pampa and Mapuche weaving.

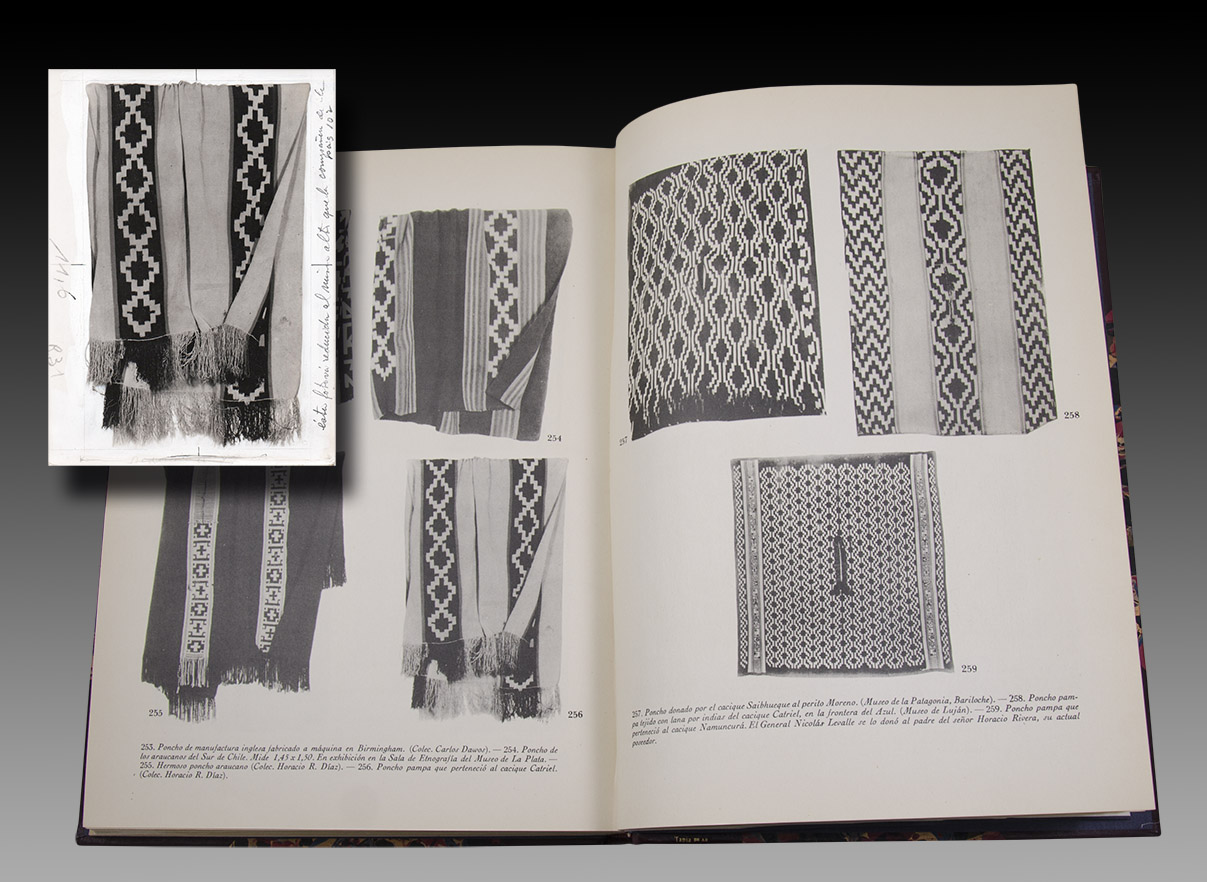

The pampas ponchos from Azul were always far superior to the Chilean ones in terms of fabric, offering extraordinary flexibility, softness to the touch, resistance to humidity and water, and low weight in relation to volume. To say in those years that a poncho was from Azul meant to express an affirmation of excellent and recognized quality. In the Museum of Luján there is one on display that belonged to Horacio Ramón Díaz whose indicative sign reads as a warning of quality: «Pampa poncho woven with wool by the Indian women of Catriel, on the border of Azul»[15 ].

And in the Ethnographic Museum of Azul there is another one with a typical drawing and colored lists, dating from 1878, whose owner – Evaristo Giménez, a former rancher in the area – used it for many decades and yet, despite the winds, suns , downpours and trajines suffered in continuous walking through the fields and ranch stoves, it could be said that it had just come out of the hands of the weaver, because despite its prolonged use it presents a new appearance, without faults of breaks in the threads, it compacts the weft and fresh its colors.

These conditions of excellence of the ponchos from Azul, displaced later by the superior ones of the vicuña ponchos of the Catamarca looms, gave them great fame and an extensive and sustained market in the 19th century.

The money

The textile fiber generally used was sheep's wool. In some observations on the border line, and in particular on that of Bahía Blanca, published in Buenos Aires in 1828, it is mentioned that «There are in the day, says a publication of the time, about two thousand Indians between adults and children in our bosom, of which there is already a large number distributed in different rooms and in the outskirts of the city. The men got together on the farms, apart from cattle, others take care of skinning otters and there are also many busy in our brick ovens. The women shear the sheep, weave jergas and ponchos» [16]. The existing documentation in the General Archive of the Nation offers us many details. A few months before the founding of Azul, at the end of October 1832, the pampas caciques Tacumán, Calfiao, Chanabil, Calfiao Chico, Antuán, Canuanté, Güilitru, and Petí camped with their sheepfolds in the vicinity of Tandil [17]. From San Miguel del Monte, Vicente González wrote to Rosas on July 17, 1833, regarding the friendly tribe of Tapalqué, who planned to send them a consignment of more than 500 fat mares, but that «In addition to that I have bought 80 arrobas of wool from the other side of the Salado and I hope that there will be an opportunity to send them to the Chinese, because the one who has gone to take the wines to the Tapalqué Indians has taken eleven days to arrive from the Salado, and this was with a change of oxen. In the matter of sheep I have done nothing for now because I see the impossibility with which they can be managed, until the roads are in a state to be herded, and then we will enter this business» [18].

Sometimes, the indigenous women directly received the wool necessary for their work, as González wrote to Rosas, from the same point, on September 5, 1833: «I have sent the women of Catriel and Cachul, with Lorea cloth blankets and some bills: the wool that I indicated to you was also» [19]. Federico Barbará, who was a frequent visitor to the awnings of Cacique Maicá, says that the weavers used the woolen thread in the blankets and ponchos for the men. After the fall of Rosas and even in the first half of the 20th century, sheep's wool continued to be used. Kermes observed in 1885 and 1887 that in the Río Negro valley they preferred pampa sheep's wool for the manufacture of ponchos and chiripaes because it made them almost waterproof, while they used merino wool, because it was softer, for the bottoms and overlays [20].

In the Museum of Luján there is a silk band woven by the wife of Cacique Catriel that belonged to Juan Manuel de Rosas. And it does not seem that, like the southern tribes, they had used the guanaco band [21].

Wool washing, degreasing and carding.

Dellepiane observed that after shearing the sheep, foreign bodies were first separated from the wool, then it was disentangled by carding it (an operation called “trucunar”) and washed with natural water to later be submerged in a container with fermented human urine whose ammoniacal content dissolved fat. Again washed with natural water and once dry, it was carded by hand.

Spinning, twisting and winding of wool.

It was then spun on a wooden "spindle", called a "chapul" about 25 centimeters long and with sharp ends, set in a "tortero" of the same material. Taking it in their right hand, they held in it some strands of the portion of wool that they held in their left hand, and turning it, they twisted the strands forming a single uninterrupted and even thread, which they wound around the body of the chapul and tied at its upper end by middle of a loop. To join two ends of thread, they twisted them by rubbing them between the index finger and thumb. With the twisted thread resulting from this operation they formed balls destined to be dyed, or to warp directly, depending on the case. The spinning operation was called "Féun", the twisted thread "Wiñifeu", and the winding operation of the thread is called "Tukum".

The Poncho Loom.

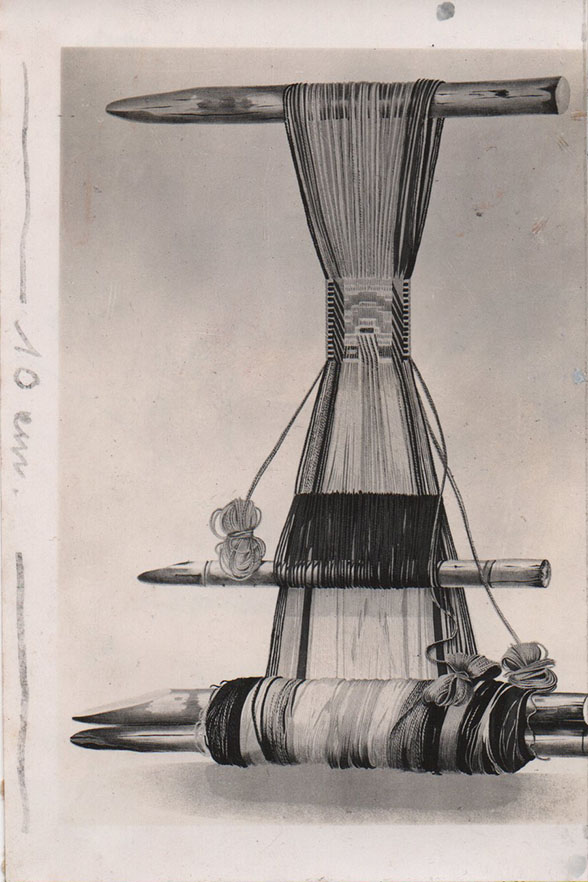

Armaignac observed in 1870 the women of the Catriel tribe busy working on their looms, made up of some pegs driven into the ground, which served to crisscross the threads, which they skillfully executed to form the drawings [22]. The loom that Armaignac saw was rectangular, like the one used in Villa Fidelidad (called "Ucha uchal"), about two meters long by one and a half meters wide: made up of two long poles resting vertically on the ground, as if of uprights, and slightly inclined backwards, and two others, or crossbars (called "Këló") of the loom, crossed horizontally that supported the warp and that with the previous ones formed a rectangular frame or frame with the necessary amplitude to weave a poncho, a woman's blanket or matra [23 ].

Dimensions

The pampas ponchos that Alcides D'Orbigny observed in 1828, formed by two parts or portions that were joined, were "seven feet long and two wide" [24]. Kermes assigns the poncho of usual dimensions 2 meters long by 1 ½ wide [25]. P. Tavella in 1924 considered that the poncho pampa was shorter and narrower than the poncho criollo [26]. There are between 1.40 and 1.90 long by 1.20 to 1.80 m. wide, but from Azul are generally 2 m. long or high by 1.50 m. wide (as Kermes maintains of the ponchos he saw in Río Negro), they had an opening in the center and fringes between 7 cm. and 10 cm. at its anterior and posterior borders [27].

As for the fringes, they exist only on the two shorter sides of the poncho as they are the result of twisting, two by two, the excess threads of the warp; although many ponchos do not have fringes.

Warp Preparation

Chroniclers and travelers who, in the mid-19th century, had the opportunity to see the tolderías near Azul and appreciate the fabrics generally confine themselves to the simple mention of the industry -the looms- in its relationship with the indigenous clothing or the trade to which it gave rise. place, but they do not provide illustrative data that allow establishing the procedures and various aspects of that industry and assessing the quality of its results. Thus, Mac Cann, in the text that we have already cited, saw in the awnings of Tapalqué (1847) dexterous and skillful women who weaved, stating that "the work is cumbersome and long because they pass the thread through the warp, with fingers, and thus it is explained that they lose a month to make a garment that, in Yorkshire, could be knitted in an hour". on his loom." Armaignac limits himself to telling us that he observed (in 1870) the women of the Catriel tribe, two leagues from Azul, busy working on their looms, made up of a few stakes driven into the ground, which were used to crisscross the threads, a task that they executed skillfully to form the drawings.

Nomenclature and arrangement of the different parts that make up the Araucanian loom, called "huitral". (Repr. of “The Araucanian fabrics”, by Claude Joseph). In Indigenous Fabrics and Ponchos of South America, by Alfredo Taullard. The image shows the original sketch used by Tallard to reproduce in his book. (Hilario Collection)

The explanation about the technique and procedures used by his descendants in Villa Fidelidad, is referred by Dellepiane Cálcena. To work more comfortably, they placed the loom (as can be seen in the graph that said author reproduces) in a horizontal position. Between the rods a and a´ and parallel to b and b´, they placed two firm ropes (warp-bearing ropes). The end of the thread that was to form the warp was knotted in the cord c', at point e, and leading it upwards they passed it through the cord c and from there they returned to the cord c'. In this way, they continued passing the thread from one cloth to another. To prevent the cords that carried the warp due to its tightness from sagging, they placed equidistant threads from the aforementioned cords to the rods b and b´. The graph distinguishes both sets of threads with the letters d and d´. At the end of tracing the warp, the end of the thread that formed it was knotted to the rope c' and to the rod a'.

Colors and dyestuffs.

D'Orbigny noted that by 1828 the pampas were making excellent woolen ponchos "adorned with very original drawings and dyed with not very bright but very solid colors." resort to casuistry based on the existing documentation in the General Archive of the Nation. Thus, for example, in an affiliation of Manuel Acevedo, dated in Azul on March 2, 1846, it was recorded that the person named wore a “pampa blanket poncho with blue stripes and punctured”, and indistinctly one or the other as a chiripá [29 ]; the justice of the peace of Bahía Blanca informed the commander of Fort Independencia, on March 13 of that year, that the Indian deserter Justino Hidalgo was wearing a “purple pampa blanket” [30]; and «poncho pampa», without any other reference, appears in the description of the clothing of the rescued captive Pablo Cortés, presented in Azul in 1847 [31] although sometimes the Indians used «pampa shawl of poncho» [32].

But the ornamentation of the ponchos from Azul at the time of the greatest commercial traffic, a decade later, did not have any richness of colors or drawings. In most cases, the only color that prevailed in the drawings was the natural white of the wool on the background of the ensemble dyed black, or dark blue, or red, accompanied by stripes of the latter color when the background had any of the first.

Sometimes, the natural colors of the wool were used, using black and white sheep, since Zeballos says that when passing through Sierra Chica in November 1879, he saw that on its slopes "small flocks of black sheep of the Indians of Cacique Catriel were grazing" [ 33].

Pampas weavers did not have procedures for bleaching, but they did have procedures for dyeing. Armaignac observed in 1870 that the colors used were mainly blue, yellow, red and chestnut or brown and that the dyestuffs were extracted from the roots, bark or fruit of various plants (although he does not tell us which ones). , a detail that Kermes does not provide either). To obtain the blue they used indigo (dark blue paste that was obtained by maceration of the stems and leaves of this plant in water), which was sent by the government [34], and to fix the color they used human urine as a mordant, which which explained the strong ammoniacal odor given off by the new ponchos [35].

Those observed by Dellepiane in 1957 and 1960 were dyed dark blue, which they obtained by infusing acacia leaves or with indigo and fermented urine as a mordant, and in certain cases in black, with industrial anilines.

Preparation of the comb.

Once the process of dyeing the wool was finished, they arranged the warp again on the loom and proceeded to assemble the comb of the loom (called "tonón"), an instrument that facilitated the task of crossing the two planes of warp threads, before and after the plot pass.

This work was done by joining the end of a long cord to the first thread on the left of the back plane of the warp and passing it forward through each of the threads on the front plane, leaving the original crossing below and taking the last thread by means of of a loop The resulting loops had to be the same length and as many as there were spaces on the front plane, and were joined by means of woolen threads passed crosswise to a wooden rod. By taking the comb and pulling forward, they crossed the two planes of warp threads; those on the rear plane passed between those on the front plane and vice versa.

Dithered.

The end of the thread that served as the weft (“Tonón uchal”: weft) was attached to the first warp thread at one point, and it was passed to the right through the free space left between the two warp thread planes. To make this task possible, they placed the shovel («Ñerewe»: shovel to press the wool) on edge, which kept the separation even. They crossed the two planes of the warp again and adjusted the pitch of the weft and the crossing with strokes of the blade. They turned the weft to the left and continued in this way, from one end of the warp to the other, alternating with the aforementioned crossings and adjustments. The regularity of the fabric and its quality depended on this work carried out neatly. The weft of these ponchos ("Tiwewe": weft threads) is tight, as is the warp. The opening to pass the head (“Pilél makuñ”: opening of the poncho) was achieved by weaving with two threads, from the edges of the warp to the middle and from this again to the edges. They plotted in this way while the opening should last, to continue as before at its end. To give it more resistance in use, they overweaved the edges of the opening with fine woolen threads.

The dyed.

Usually the wool was dyed in skeins, according to the bands or lists of different colors of the piece that was intended, but also, and this was already observed by Armaignac, everything was woven in natural-colored wool and then the entire piece was dyed when this was going to receive a single color, or the white drawings that formed crosses and diamonds or circles were reserved by means of knots, so that they would not be affected by the color of the dye and they would remain unpolluted [36]. Both decorative motifs (which respond to the two negative-dye decoration techniques used by Pampa weavers and known since pre-Hispanic times: ikat and plangi) coincide with those observed by Kermes around 1887 in the Río Negro valley [37].

Ring poncho of Cacique Catriel. Vintage photography was studied by Alfredo Taullard. Hilary Collection.

Pampas ponchos impermeability.

The extraordinary impermeability of pampas ponchos to rain has been highlighted by D'Orbigny [38], Armaignac highlights as quality notes of the pampas textile industry of 1870 that the colors were unalterable, the fabrics long lasting and almost waterproof. to water [39]. And Kermes [40] highlights this characteristic that, to a lesser degree, is also observed in Chileans of the same period.

This quality would seem opposed to the material used in the clothing, since wool is very absorbent. However, the fabric with its twisted threads has a weave such that when it receives rain it becomes rigid and the water slides over the surface without going through it. The pampas used better quality wool strands, much finer and longer than those that could be supplied by Chilean sheep [41]. For his part, Manuel Alejandro Pueyrredon in 1861 affirms that «Chilean Indian women weave blankets and ponchos, with more perfection than the pampas, they use finer inks that they extract from plants they know and harvest the grana or cochineal, they know how to combine colors by mixing with each other [...] The ponchos they make are paid with respect, because they are made to resist the action of the continuous rains, the water does not penetrate them when they are thin» [42].

But the pampas ponchos were always far superior to the Chilean ones in terms of fabric, they offer extraordinary flexibility, they are very soft to the touch, resistant to humidity and water, and light weight in relation to volume. These conditions of excellence of the ponchos from Azul, displaced later by the superior ones of the vicuña ponchos of the Catamarca looms, gave them great fame and an extensive and sustained market in the 19th century.

* Expanded and improved text for editing in Hilario. Its author had already published a first version of this work in the newspaper El Tiempo de Azul, on May 20 and 27, June 3, 10, 17 and 24, 1978 with the title TEJIDOS PAMPAS DE AZUL; the second retouched and synthesized version in El Tradicional No. 42 of February 2001, entitled LA TEJEDURÍA AZULEÑA. The third, expanded, by the newspaper Pregón, also from Azul, in the Special Supplement of December 2017. And now a special update for Hilario, for the first time with the erudite apparatus; that is, the quotes and references that enrich it so much.

Notas:

1. «Museo Etnográfico de Azul», en La Prensa, núm. 22.478, Buenos Aires, jueves 10-IX-1931, sección 2ª, p. 7. «En Azul fue inaugurado el Museo Etnográfico y Archivo Histórico Enrique Squirru», en La Nación, domingo 15-IV- 1945, 3ª. sección, p. 2, con vistas fotográficas de las salas «Martín Fierro», «José Hernández», y «Sargento Cruz».

2. Carlos Dellepiane Cálcena, «Consideraciones sobre la tejeduría de una comunidad de origen araucano. Azul (provincia de Buenos Aires)», en Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Folklóricas, núm. 1, ps. 83-93 (Buenos Aires, 1960).

3. Guillermo Palombo, «Tejidos pampas de Azul», en El Tiempo, Azul, 20-V-1978, [p. 7], col. 1 a 4; 27-V-1978, [p. 7], col. 5 a 7; 3-VI-1978, [p. 7], col. 4 a 6; 10-VI-1978,[p. 7], col. 4 a 7; 17-VI-1978, [p. 7], col. 1 a 4 y 24-VI-1978, [p. 7], col. 4 a 6, cuya síntesis pero con el aporte de nuevos datos fue publicado como «La Tejeduría Azuleña», en el mensuario El Tradicional núm. 43, de abril 2001. “Ponchos y fajas de la tejeduría pampa azuleña” en Pregón. Diario Regional de la Tarde, Suplemento Especial 185° Aniversario de la Ciudad de Azul, Azul, diciembre 2017, 16 p.

4. Tomás Falkner, Descripción de la Patagonia y de las partes contiguas de la América del Sud. Traducción, anotaciones, noticia biográfica y bibliográfica por Samuel A. Lafone Quevedo (La Plata, 1910).

5. Joseph Sánchez Labrador, Los indios pampas, puelches y patagones. Monografía inédita prolongada y anotada por Guillermo Furlong Cardiff (Buenos Aires, Viau y Zona, 1936).

6. A.D´Orbigny y J. B. Éyriés, Viaje pintoresco a las dos Américas, Asia y África. Resumen general de todos los viajes y descubrimientos de Colón, Magallanes, Las Casas, Gomara, La Condamine, Ulloa, Jorge Juan, Humboldt, Molina, Cabot, Grijalba, Koempfer, Marco Polo, Forster, Chardin, Tournefort, Volney, la Loubére, Chateaubriand, Caillé, Lauder, etc., etc., vol. 1, p. 267 (Barcelona, Imprenta y Librería de Juan Oliveres, 1842).

7. Félix F. Outes, «Observaciones etnográficas de Francisco Javier Muñiz», en Physis, Revista de la Sociedad Argentina de Ciencias Naturales, vol. III, ps. 197-215 (Buenos Aires, 1917).

8. William Mac Cann, Two thousand mile´s ride through the Argentine Provinces: being and account of the natural products of the country, and habits of the people, with a historical retrospect of the Rio de la Plata, Monte Video and Corrientes, vol. 1, p. 110 (London, Smith, Elder & Co., 1853).

9. F [ederico]. Barbará, Usos y costumbres de los indios pampas y algunos apuntes históricos sobre la guerra de la Frontera, p. [v] de la Advertencia (Buenos Aires, Imprenta de J. A. Bernjeim, Calle Defensa, 73, 1856).

10. Abelardo Levaggi, Paz en la frontera. Historia de las relaciones diplomáticas con las comunidades indígenas en la Argentina (Siglos XVI-XIX) (Buenos Aires, Universidad del Museo Social Argentino, 2000).

11. William Mac Cann, loc. cit.

12. V. Martin de Moussy, Description géographique et statistique de la Confédération Argentine, t. II, ps. 486-487 (Librairie de Firmin Didot Frères, Fils et Cie., 1860); t. III, ps. 65-66 (Paris, Librairie de Firmin Didot Frères, Fils et Cie., 1864).

13. José María Araya – Eduardo Ferrer, El comercio indígena. Los caminos al Chapaleofú (Tandil, Municipalidad de Tandil y UNCPBA, 1988).

14. Héctor Pedro Blomberg, «Los catrieleros del Azul», en Caras y Caretas, año XXXV, núm. 1860, Buenos Aires, 26-V-1934.

15. Alfredo Taullard, Tejidos y ponchos indígenas de Sudamérica, figura 258 (Buenos Aires, Peuser, 1949).

16. Cfr. Observaciones sobre la línea de fronteras, y en particular sobre la de Bahía Blanca, Buenos Aires, Imprenta del Estado, 1828 (1 vol. In 4º de 9 ps.). Publicadas en los Nº 151 y 15 del Correo Político (1828).

17. Felipe Pereyra, comandante del Fuerte Independencia, a Juan Manuel de Rosas, Tandil, 31-X-1832, en Archivo General de la Nación, Buenos Aires [en adelante AGN], Sala X, legajo 24-7-3.

18. Vicente González a Juan Manuel de Rosas a Juan Manuel de Rosas, Monte, 17-VII-1833, en Celesia, Rosas, aportes para su historia, t. I, p. 572 (Buenos Aires, Goncourt, [1969]).

19. Vicente González a Juan Manuel de Rosas, San Miguel del Monte, 5-IX-1833, AGN, Sala VII, legajo 22-1-1 (Colección Ernesto Celesia); Celesia, Rosas, t. I, p. 598.

20. Enrique Kermes, «Tejidos Pampas», en Revista del Jardín Zoológico de Buenos Aires, dedicada a las Ciencias Naturales y en particular a los intereses del Jardín Zoológico, tomo I, entrega VI (15-VI-1893), p. 179.

21. Cfr. Mariano Ruíz a Martín de Gáinza, fechada en Patagones el 17-X-1871 (AGN, Museo Histórico Nacional, Leg. 41 [Archivo de Martín de Gainza], doc. núm. 5776)

22. H. Armaignac, Voyages dans les Pampas de la République Argentine, p. 257 (Tours, Alfred Mame et Fils, Éditeurs, 1883).

23. Véase la fotografía de un telar vertical empleado en Villa Fidelidad en 1928, en Azul. Revista de Ciencias y Letras, núm. 5, entre ps. 192-193, Azul, Impr. Placente & Dupuy, 1930.

24. D´Orbigny y Éyriés, Viaje pintoresco…, vol. 1, p. 267.

25. Kermes, «Tejidos pampas», p. 183.

26. Roberto J. Tavella, Las misiones salesianas de La Pampa, p. 54 (Buenos Aires, Talleres Gráficos Argentinos Rosso y Compañía, 1924).

27. Susana Chertudi y Ricardo Nardi, «Tejidos araucanos de la Argentina», en Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Folklóricas, núm. 2, p. 159, Buenos Aires, 1961; Dellepiane Cálcena: «Consideraciones …», fotografías 1-17, 19 y 20; Azul. Revista de Ciencias y Letras, núm. 5, fotografía entre ps.184-185 y 188-189.

28. D´Orbigny y Éyriés, Viaje pintoresco…, vol. 1, p. 267

29. AGN, Sala X, legajo 20-10-2.

30. Archivo Histórico de Azul, Año 1846, N° 37.

31. Descripción de la vestimenta del cautivo rescatado Pablo Cortés, presentado en Azul en 1847, AGN, Sala X, legajo 20-10-2.

32. Descripción de la vestimenta del cacique Necul, prisionero, fechada en Azul en 1847, en idem.

33. Kermes, “Tejidos pampas”, p. 180. Estanislao Zeballos, Viaje al país de los araucanos, p. 51 (Buenos Aires, Imprenta de Jacobo Peuser, 1881), refiere que al pasar en noviembre de 1879 por Sierra Chica vio que en sus faldas «pastaban pequeños rebaños de ovejas negras de los indios del cacique Catriel».

34. Para obtener el azul usaban añil, pasta azul oscuro que de los tallos y hojas de esta planta se obtiene por maceración en agua. Sobre este arbusto véase: Angel Marzoca, Historia de plantas tintóreas y curtiembres, ps. 156 a 173 (Buenos Aires, Colección Agropecuaria del INTA, vol I, 1959).

35. Armaignac, Voyages ..., p. 248.

36. Armaignac, Voyages ..., p. 247.

37. Ambos motivos, que se expresan coinciden con los observados por Kermes hacia 1887 en el valle del Río Negro. Cfr.“Tejidos pampas”, ps. 185 (fig. 20) y 186 (fig. 21).

38. D´Orbigny y Éyriés, Viaje pintoresco…, vol. 1, p. 267.

39. Armaignac, Voyages…, ps. 247-248.

40. Kermes, «Tejidos pampas», ps. 179 y 186.

41. Enrique Wernicke, «Apostillas a la historia del ganado lanar argentino. Las ovejas pampas, criollas y chilenas», en La Prensa, núm. 22.975, Buenos Aires, 22-I-1933, secc. 3ª, p. 3.

42. Manuel A. Pueyrredon, Memoria sobre la Escuela Militar dedicada al Gobierno Nacional, p. 37 (Buenos Aires, Imprenta de Bernheim y Boneo, 1861).