June 9 marks International Archives Day, an event proclaimed in 2008 by the International Council on Archives to remember that, on that date and in 1948, UNESCO created this international non-governmental organisation with the aim of promoting the management and efficient use of documents, as well as the preservation of the evidentiary and cultural heritage of humanity.

Archives, a space where different knowledge converge, contain, in fact, the history of their formation, as well as of access to information and the intellectual practices linked to them. Although the “archives” of the palaces and the cartularies are older, in the 16th century the idea that they were the arsenals of authority was imposed, this in a context that, linked to the renaissance of Roman law that began in the 12th century, was characterized by the growing use of the written document by government institutions and by the diffusion of national languages and paper or cloth parchment. As several authors have indicated, the archive did not have, either in its origin or in its function or objectives, a cultural mission: having the information stored there was a discretionary power of the Monarch, who granted or denied this privilege according to his will and interests.

In the 19th century, on the contrary, the archive was consolidated as a laboratory of history, at a time when dispersed government repositories were collected to place them under a unified safeguard, linked to the general interest and to a supposed memory of the nation. From then on, access to it accompanied the democratisation of the State and the creation of spatial order systems that guaranteed it: catalogues, files, archives and furniture related to these purposes.

The 21st century celebrates digitalisation and access through databases and the internet, as well as the expansion of the funds and people whose collections are preserved. If in the 20th century the archives of the history of work were added, the documents that are kept today are as numerous as the varied panorama of written and visual culture in two dimensions and in digital version that is archived today.

Not long ago, on June 9, the T. Navarro Tomás Library of the Center for Human and Social Sciences of the Spanish CSIC (the equivalent of our CONICET) gave an example of this by celebrating the day with the María Isabel Navarrete Navarrete postcard collection, a collection dating back to the first half of the 20th century that I discovered thanks to my friend Maribel, a prehistorian from Madrid, namesake of her maternal great-aunt and daughter of Dr. Antonio Martínez Echeverría. The custodian of the album that contained them, after organizing them and completing them with information transmitted in the family, she handed them over to the postcard collection of the Photographic Archive of the library of the Center where she worked as a researcher until her retirement and which today proudly displays them.

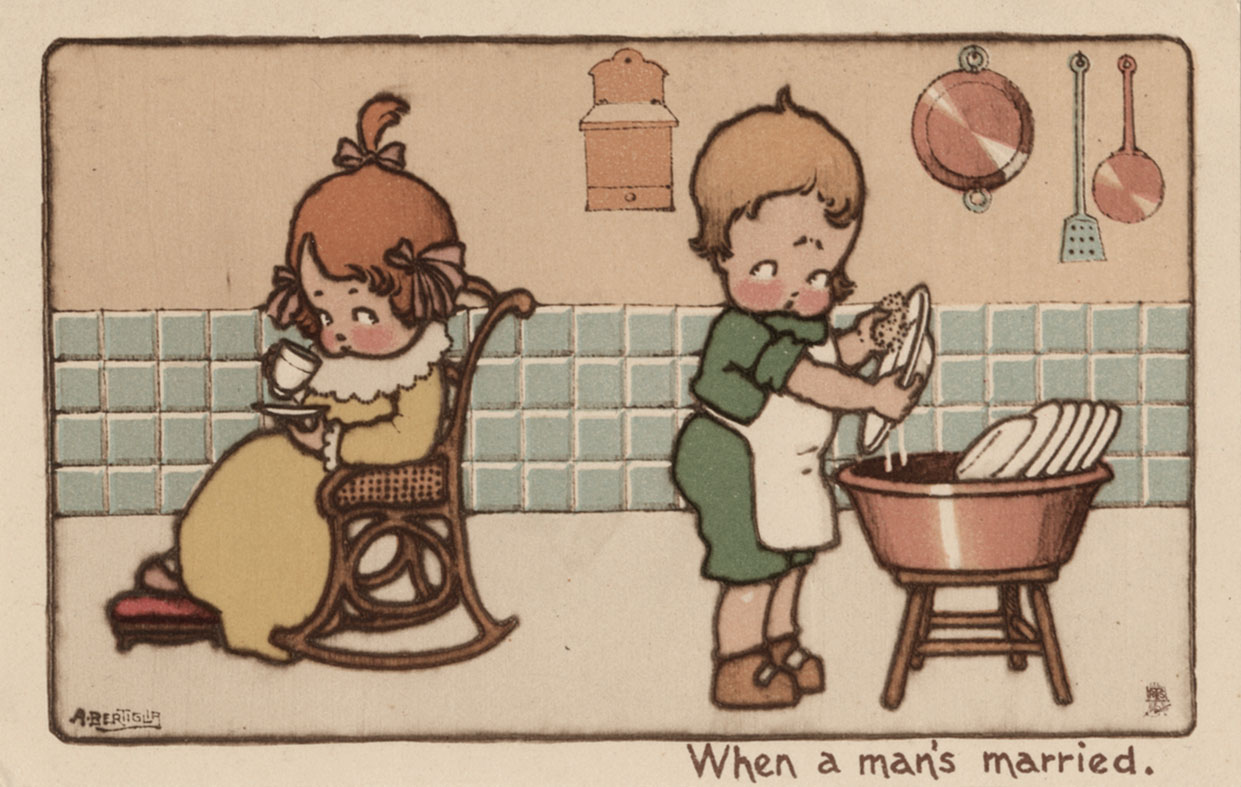

By using them to celebrate International Archives Day, the Navarro Tomás Library intended to promote the presence of this type of material in graphic and photographic repositories, showing the aspects of the postcard as a cultural object, a means of communication and an instrument for the dissemination of ideas, values, tastes or fashions in the different periods in which they have been used. In this case –say those responsible for the Library's Photographic Archive– the dates range from 1910 to 1961 and "allow us to learn about María Isabel's personal and family history, the links she established with a collecting purpose, and the postcard industry so in vogue in those years, as a reflection of the society of the time."

The collection is made up of 243 postcards, some of them written and circulated, that María Isabel collected since her childhood. They were sent to him by his brothers, his father, his cousins, friends and relatives who knew of his fondness for collecting postcards, a collection that reflects the family history and the history of the postcard in an era marked by the Great War and the rise of Francoism. The themes are drawings dedicated to a child or young audience, but with varied content. Many extol patriotism and encourage enlistment in the army to fight in the Great War: "Without weapons, you will not have a girlfriend," says one of the cards published by an English printing house enrolled in mass recruitment campaigns, putting pressure on young people through female figures that express their admiration for soldiers and their rejection of civilians. Others praise love, marriage, family, children's games, animals, celebrations such as Easter, with a markedly educational intention. There are also landscapes and views of cities.

The collection also includes family portraits; here Carlos Finlay, in a record taken in Havana, Cuba. English:Photograph: Courtesy of the T. Navarro Tomás Library of the Center for Human and Social Sciences of the CSIC (Spain).

María Isabel del Socorro Navarrete Navarrete, “Nena” (Madrid, 1906 -1995), was the daughter of Joaquín Navarrete y Alcázar (Havana 1859 - Madrid 1929), Commander of the Marine Infantry, and María Elisa Navarrete y Finlay (Havana 1864 - Madrid 1928). In that branch, she was the great-niece of Carlos Finlay (1833-1915), the Spanish doctor, born in Puerto Príncipe, today Camagüey, one of the first to recognize that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, who, in the family, was the godfather of Octavio Augusto Carlos (Havana 1891 - Madrid 1944), the second son of Joaquín and María Elisa, with whose family Nena lived after the death of her parents.

Another of his brothers, Gabriel (Madrid 1898 - Larache, Morocco 1925), was a legionnaire in the African War, a member of the first group to arrive in Ceuta, from where he sent a series of photographs to his parents and siblings, including one of the day the Legion was born on 20 September 1920. In the centre is José Millán-Astray y Terreros (La Coruña, 1879 - Madrid, 1954) who, interested in creating a corps of foreign volunteers similar to the French Foreign Legion, had visited Algeria to study how the French army's corps worked. Millán Astray not only founded the Legion and Radio Nacional de España: he was a procurator in the Francoist Cortes between 1943 and 1954, a personal friend of Francisco Franco and head of the Benemérito Cuerpo de Mutilados de Guerra por la Patria front. Gabriel, on the other hand, would die in Morocco and would not live to see any of this.

However, her younger sister's collection continued to grow and includes cards from the United States, the United Kingdom, Cuba, Germany, Ireland, and Spain. Some were sent by family and friends, from their travels or from their places of residence. In other cases, they were purchased in bookstores or "bazaars" that sold their own editions or those made by other establishments, both national and foreign.

There are a good number of postcards that were exchanged between family members and their loved ones, but which were given to María Isabel to increase her collection. Some come from the Cuban branch. Part of it, linked to the Royal Navy and the Marines, had to leave the island with independence, while others remained in the Caribbean. Hence the maternal grandmother's interest in bringing up to date the congratulations and the importance of "Nena's" trip to Cuba in 1926 and 1927. In this sense, the texts written on the cards identify the name days and birthdays, with which the postcards fulfilled a double mission, connecting and helping the growth of the collection. The group of postcards in the album increased in the first years both on the maternal side (the Cuban line of the Finlays and Barrès) and on the paternal side (Navarrete Alcázar brothers) with occasional extensions to family friends and cousins.

Published by the firm Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, of Florence. Photograph: Courtesy of the T. Navarro Tomás Library of the Center for Human and Social Sciences of the CSIC (Spain).

Among the publishing houses of the postcards in the collection are Inter-Art Co., Raphael Tucks & Sons, The Carlton Publishing Co., C.W. Faulkner & Co. and James Henderson & Sons, all five based in London although Carlton printed in Germany; Henry Heininger, Reinthal & Newman and Edward Gross of New York; the Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini of Florence; Wilhelm S. Schroeder (Max Wollstein) of Berlin; N. Coll Salieti of Barcelona; Meissner & Buch of Leipzig; and a German concession from Walt Disney. Many of them are illustrated by such leading artists in the publishing industry as Frederick Spurgin, Pauli Ebner, Aurelio Bertiglia, Mabel Lucie Attwell, Donald McGill, Bessie Pease Gutmann, S. Hurley, and C.H. Twelvetrees.

Postcards are a quintessentially mobile object, but the list of these people and companies reminds us that loyalty to the flag can be printed with enemy ink and that things and customs do not move alone but with the help of money and capital. Thus, Raphael Tuck (1821-1900) and his wife Ernestine, the English publishers of greeting cards, moved to London from Prussia around 1860 and their three sons, Herman, Adolph and Gustave, and two grandsons, Reginald and Desmond, continued to run the business with branches in Paris and New York, until around 1960, the company merged with others to become the British Printing Corporation.

The Swiss historian Jakob Tanner has pointed out the bureaucratic and creative power of the archive, since the files have the capacity to shape the identities and actions of the subjects. In that logic, one is who the records say one is, was and will be. A collection of postcards like Aunt Maria Isabel's reminds us, moreover, how companies – in this case publishers and printers – have the same or perhaps more capacity to create habits, poses, grimaces and obsessions, mobilizing people to go to the post office on both sides of the sea and the ocean to wish happy birthday or happy Easter, always with the same phrases, the same gestures, buying a postcard, a stamp and connecting them with each other by a childish mania that, in the end, was never spontaneous.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades