On “Fire makes no concessions”, a work by Carlos Runcie Tanaka

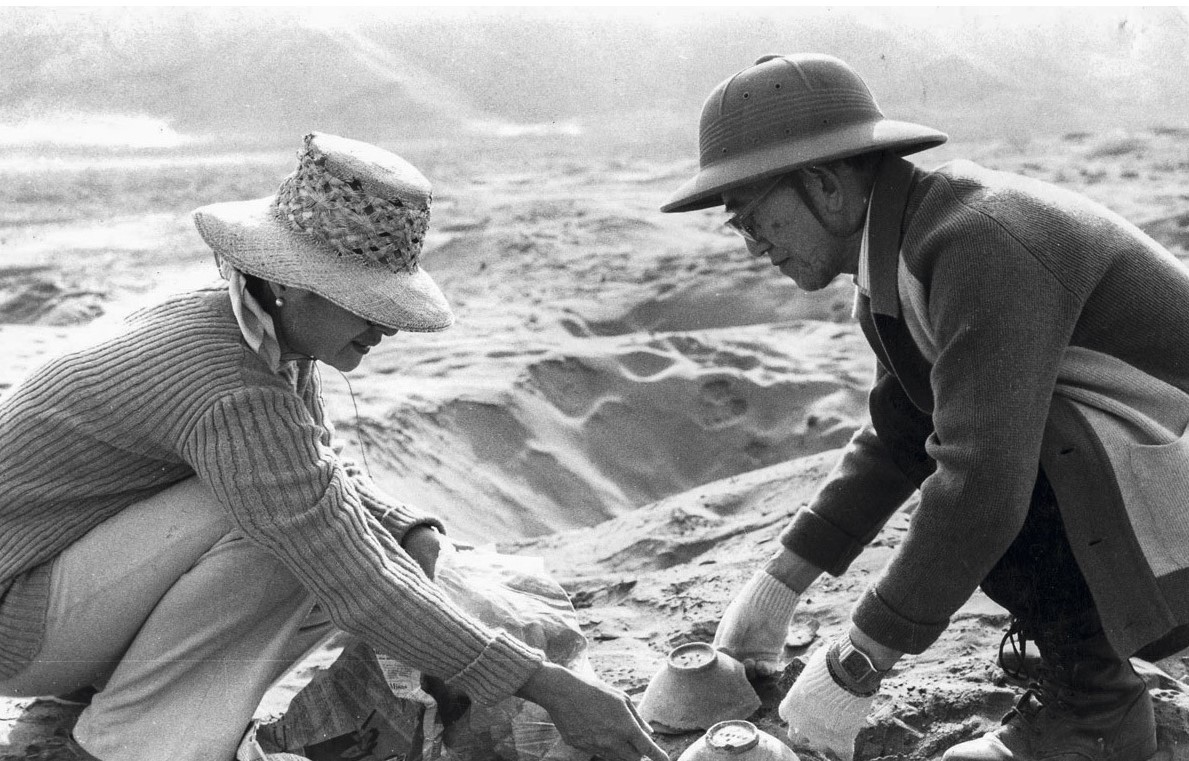

A few years ago, the Lima artist Carlos Runcie Tanaka [b. 1958] made an installation at the Amano Pre-Columbian Textile Museum in Lima. A private museum dedicated to exhibiting the collection of Yoshitaro Amano [1898-1982], a Japanese engineer living in Peru interested in the antiquities of his adopted country. Among the pieces collected, one series is a rarity: Amano, with a technical eye, collected not only the works that stood out for their workmanship but also those that, when fired, were transformed into something different than expected. I say with a technical eye because these exhibits also spoke of the limitations of knowledge and experience, of the failures and unpredictable effects of any production process.

On that occasion, Runcie combined the exhibition of these pieces from the old Chancay kilns with his own works scorched by the fire in his workshop. The following text is a reflection on them.

***

In the work of Carlos Runcie Tanaka there is a theory of the Earth. Or two, three. Maybe five. Many, many, as many as there are hands, eyes and trades, have been dedicated from the Neolithic to today, to thinking about the balance between solid and liquid, between the forces of heat and cold. Without exaggeration, the potter's laboratory seems to have given shape to the hypotheses to explain or understand the formation of minerals found in nature. Or it could also have been the other way around: that the workshop of the potters of here and now, of the antipodes or of prehistory, has emerged as a mere attempt to remake, on a human scale, the chemical and physical processes hidden in the folds and colours of the Earth, in that apparent eternity of rocks, basalts and lavas.

***

As we read in the pen of Daniel Defoe [1660-1731], Robinson Crusoe, in order to survive on his island, travels through the history of humanity and, along the way, learns to bake pottery. To do so, he cheats: his attempts are not those of primitive man but of the late 17th century, where the commercial obsessions of Europeans - Jesuit spies included - are trying to get closer to the secrets of temperature and the materials required for the making of Chinese porcelain. In the heat of the race to control heat and substances, new European porcelain factories and new theories arose to explain how the planet that produced them worked.

Surviving on the island was not an easy task. Robinson Crusoe had to resort to ingenuity and to everything he had already learned in his life.

By then, the theories of Francis Bacon [1561-1626] had been discarded. In Sylva Sylvarum and his posthumous "Plan for the Particular History of Condensation and Rarefaction in Natural Bodies" he repeated the fabulous idea that the material for porcelain came from artificial mines passed down as a heritage from father to son. To do this, according to the ideas propagated in Europe, the Chinese buried a prepared mass or cement at a certain depth, which, lying for about forty years, became the precious element. And this was done by the work and grace of the hardening process [in the metallurgical sense of the term] or lapidation that could be due to cold, heat or assimilation. Thus -always according to Bacon- by hardening of the earth and clays, stones were also generated inside the Earth. Or minerals, which were nothing other than petrified juices of concrete. And diamonds, crystals and amber, not to mention that bricks, tiles and glass were made by hardening. The art of hardening, conceived as metallurgy, belonged to the natural world and to that of men.

Around 1700 – the years of Defoe – the laboratories of the Saxon mathematician and physician Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus [1651-1708] and the alchemist Johanne Friedrich Böttger of Saxony [1682-1719] led to the founding of the Meißen factory near Dresden, from 1720 the first where European white porcelain was successfully produced. Tschirnhaus's chemical and physical interests, as a frequent correspondent of French and Italian experimenters, had led him to study the melting point of various refractory substances and to experiment with the effect of high temperatures on a kind of kaolin and on asbestos and calcium and magnesium silicates. Until then, no European furnace had reached 1450 degrees Celsius, the firing temperature of true porcelain. Tschirnhaus, however, succeeded in concentrating radiant heat by means of an iron burning mirror, marking the course of experiments on combustion and the chemistry of materials that would later be taken up by the so-called plutonist theory of the Earth of the Englishman James Hutton [1726-1797].

*****

The first prehistoric potter and the first 18th century plutonist shared a premise: heat, whether it comes from human fire or from the interior of the Earth, is the cause of the creative phenomena that govern us. Far from being a destructive force, it is the origin of everything, the condition of possibility of the order of rocks, of crystals and, later, of life. Without fire, there is nothing. But, for many inhabitants of that century, terrestrial processes were associated with the power of water and a solid, cold crust. For the plutonists, on the other hand, the unknown lay in questions such as at what depth, to what extent and with what intensity did the heat act; or, in other words, how to prove that the solid rocks of today, thousands and thousands of years ago, had a different nature.

The 18th century plutonists did not know, however, how to calculate the force and intensity of underground heat. There was no definitive evidence of its existence: the expansive and driving power housed in the bowels of the planet was manifested in ordinary experience through hot springs, volcanoes and earthquakes. The intensity of volcanic fire favoured the opinion that it was deep in the earth's surface, but its dimension and power had to be demonstrated. This was the aim of the essays of the Scottish baronet James Hall [1761-1832], a geologist and chemist who, based on experimental models, considered temperature to be the crucial factor in understanding the genesis of igneous rocks. To do this, he turned to the progress of the English ceramic factories, which had not only managed to break the Chinese monopoly on the porcelain trade but also invented a device to measure the heat of the oven and thus control the firing of the pieces.

Hall, who was studying the fusibility of basalt and lava, did in fact turn to the pyrometer designed by Josiah Wedgwood [1730 - 1795], a manufacturer and heir to a family of potters, the future grandfather of Emma, Charles Darwin's cousin and wife, the grandson of Erasmus, the poet friend of Josiah. In the 1770s, J. Wedgwood had begun to register his interest in the problem of how to measure high oven temperatures beyond the possibilities of mercury thermometers in order to improve the quality of his products. Although he had first thought of resorting to the systematic observation of the phenomenon of the progressive change in colour of clay mixtures when subjected to heat, in 1781 he developed a ceramic pyrometer, presented to the Royal Society in May of the following year: a clay cylinder that took up the property of these pastes of decreasing in volume under the influence of heat. This pyrometer was introduced into the oven along with the firing and allowed the melting point of copper, silver, gold and iron to be calculated [with errors].

Vase. Ceramic paste. 1775 - 1800. Ceramic paste. Author Josiah Wedwood, considered the best English ceramist of all time. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Bequest of Pedro Fernández Durán and Bernaldo de Quirós, 1931. Photograph: Courtesy of the Museo del Prado.

Hall's experiments, for their part, began in 1798, 16 years after the introduction of the pyrometer to scientific and industrial circles in London. The results were published in 1806 and hailed as relevant not only to geology but also to chemical science in general. The fact that the most refractory substances could be melted by suppressing the elasticity of the gaseous parts contained in them illuminated the operations that governed the mineral kingdom and improved knowledge of the action of fire, promising a substantial increase in the power that man had acquired over that element.

The ceramist's furnaces and instruments had served to demonstrate that the rocks in question melted at a temperature similar to those of art and industry. And the properties of clays, used to govern production and the commercial conquest of the world that was opening up to science, progress and English domination of the table of proletarians, aristocrats and bourgeois.

****

The control of fire continued to be a concern for ceramists and geochemists. Pyrometers, despite the great hopes generated by their introduction and their use to understand the forces of the planet, did not meet the conditions necessary for industrial manufacture. That is, they were difficult to use, they reported imprecisely and slowly on the temperature and progress of the fire in the kiln, and the data provided were incomparable: they barely transcended the national scale. That is, the English one.

For this reason, attempts at absolute measurement had to coexist with the observation of incandescence also evoked by Wedgwood and known since the dawn of sedentary life: to judge fire - said the French manuals of the beginning of the 20th century and the works of Runcie Tanaka confirm it - you need great experience, a look acquired after many years, looking at the draft, the length of the flame, its more or less bluish colour and the soot. After all, a good potter – in Peru or Japan – knows that when the parts of the kiln begin to turn red, the colour of the fire must be examined through the kiln openings and that the shiny state of the pieces can provide the means to judge their strength and regularity. Or else, as the temperature rises, direct samples of clay and glaze are taken from the kiln in order to check the vitrification of the materials. And then decide on the steps to follow.

But, in order not to be left behind in the search for the universal, the different degrees of incandescence corresponding to the temperatures were systematized in tables and other gadgets were invented, as artisanal as mere pottery: small pieces with the name of clocks or pyroscopes, of the same nature as the ceramics to be fired, placed in various places in the kiln and which, removed towards the end of the firing, are examined to determine the colour/temperature scales.

However, observing the colour of the fire is sometimes not enough, or, on the contrary, it is used, as Runcie Tanaka does, to burn the pieces, calculating the hours of firing and the [almost] unpredictable results of the risk that this calculation entails. Experience can take things to that melting point from which there is no return, to those 1451 degrees Celsius –just one more- where the shape of the porcelain collapses, where the fitting of the pieces in the oven results in the creation of a single one. As in basalt, lava, flies inside amber, petrifications, Bacon's lapidations. Because in the end, after the excesses of heat, the substances cool down and the form appears. Another one. Curious that these "errors" are known as waste. Perhaps to highlight that ceramics, once fired –unlike glass or metals– cannot be recycled to produce new ones. Curious fate of this material that, whether we wanted it or not, helped us to think about the creative dynamics of the Earth.

****

Perhaps the awareness of the irreversibility of the destruction caused by an excavation and the works of men made the engineer Amano gather waste, scraps, leftovers. In times when only precious metals and elaborate ceramics were valued, he dedicated himself to the leftovers from graveyard ventures: fabrics and Chancay pottery, seen as the most "rustic and simple" of the pre-Columbian universe. Amano - a castaway of the 20th century - did not disdain the effects of the uncontrolled fire, a sign of the failures of the industry but also a possible sample of the experimentation with the materials and forces of pre-Columbian times. And of the threads and processes that have woven and shaped the world.

Because, in the end, "Fire makes no concessions" convinces us that being a ceramist or potter is equivalent to experimenting with the formulas and forces that shaped the planet and the human experience. And, as Carlos Runcie Tanaka knows well, to reflect with the hands and with the eyes, on the origin, the change and the itineraries of the matter.

* Special for Hilario.

Robinson Crusoe potter

[From Daniel Defoe, Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719)]

But, this was not my main work, but rather, a hobby that amused me while I occupied my hands in other tasks, like the following. I had studied for a long time the way to make some clay vessels, which I needed so much, but I still did not know how. But, taking into account that the climate was hot, I did not doubt that, if I could find good clay, I could make some pot that, dried in the sun, would be strong enough to handle and keep inside anything I wanted to preserve from humidity. As I needed some such pots for grain and flour, which was what concerned me at the time, I decided to make them as large as I could, so that they would serve exclusively as jars for preserving whatever I kept in them.

Perhaps the reader will pity me, or, on the contrary, laugh at my clumsiness in making the clay and the misshapen objects I made of it, which sank inward or outward because the clay was too soft to support its own weight. Some cracked when exposed hastily to the excessive heat of the sun, others broke into pieces when I moved them, both when dry and when still wet. In short, after an arduous effort to obtain the clay, to extract it, knead it, transport it, and mold it, in two months I could make only two large and ugly things, which I would not dare to call jars.

However, when the sun had dried them to a very hard state, I carefully lifted them out and placed them in two large wicker baskets, which I had woven especially for them, so that they would not break. Between each pot and its corresponding basket there was a little space, which I filled with rice and barley straw. I thought that, if they were kept dry, they might be used to store the grain, and perhaps the flour, when it was ground.

Although I made many mistakes in my project of making large pots, I was able to successfully make smaller ones, such as basins, dinner plates, jugs, and pots, which the heat of the sun dried and made strangely hard.

None of these, however, satisfied my main need, which was to obtain a vessel into which I could pour liquid and which would be resistant to fire. After some time, one day, when I had made a great fire for roasting meat, when I was removing the coals, I found a piece of an earthenware pot, burnt and hard as a stone and red as a tile. This pleasantly surprised me and I said to myself that, certainly, if they could be cooked in pieces, they could also be cooked whole.

This incident led me to study how to arrange a fire for firing some clay pots. I had no idea how to make a kiln such as potters use, or how to glaze the pots with lead, though I had some lead to do so. I piled three large pots and two pots on top of each other, and arranged the coals around them, leaving a heap of embers beneath. I fed the fire with wood, which I placed outside and on the pile, until the pots were red-hot without breaking. When they were distinctly red, I left them on the fire for five or six hours, until I found that one of them did not break, but melted, because the sand I had mixed with the clay was melted by the violence of the heat, and would have turned into glass if I had left it there. I gradually lowered the fire until the redness of the pots became fainter, and I watched them all night, that the fire might not go out too quickly. Next morning I had three good little pots, though not very pretty, and two vessels, as strong as could be desired, one of which was perfectly glazed by the sand-casting.

I need not say that after this experiment I never wanted any clay pots which I could not make myself. But I must say that as to shape they did not differ much from one another, as might be expected, for I made them in the same way as children make their clay cakes, or as women, who have never learned to make dough, bake their pastries.

I never felt such joy over a trifling thing as when I found that I had made a fire-proof clay pot. I barely had the patience to wait for it to cool down and put it back on the fire, this time filled with water, to boil a piece of meat, which I succeeded admirably in. Then, with some goat, I made myself a very tasty broth and I would have only needed a little oatmeal and a few other ingredients to make it as tasty as I would have wished.